Executive Summary

Highlights

- Local governments across the United States have adopted ambitious decarbonization goals that rely on cost-effective clean energy procurement within wholesale electricity markets.

- Although wholesale electricity markets contain many features that provide an enabling environment for the integration of clean energy resources into the electricity grid, their evolving rules and policies can affect local governments’ ability to achieve their clean energy goals.

- Improvements to several wholesale market rules and policies can further catalyze renewable energy deployment so that local governments can meet their clean energy goals.

- Key areas for reforms within wholesale markets include transmission; energy, ancillary services, and capacity market rules; integration of new resource types; and stakeholder processes.

- Although all seven wholesale electricity markets in the United States share some commonalities across barriers to and opportunities for clean energy deployment, each market has unique characteristics and circumstances that require consideration as local governments pursue their clean energy goals.

Background

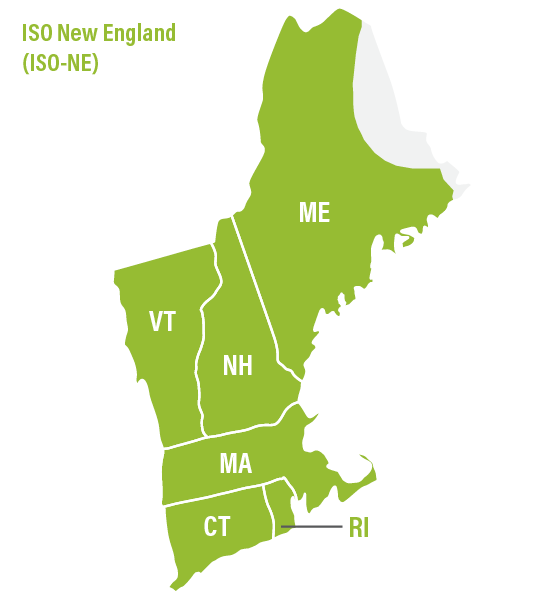

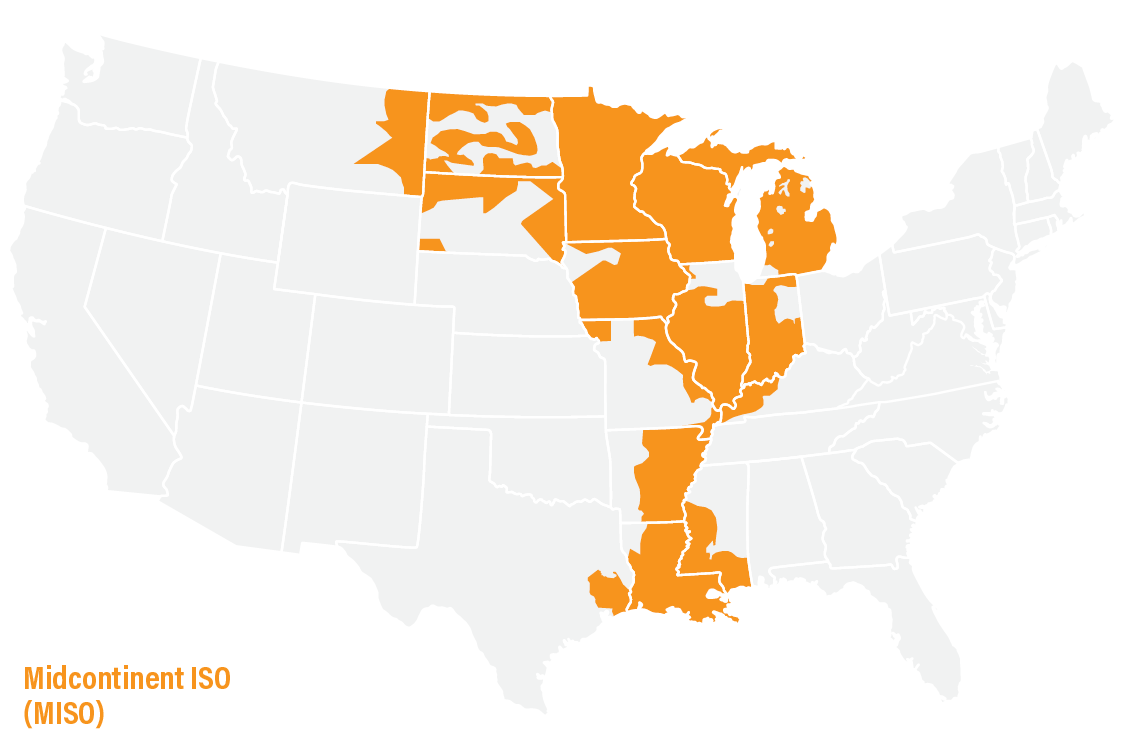

In the United States, seven wholesale electricity markets are operated by regional transmission organizations (RTOs) and independent system operators (ISOs). About two-thirds of total electricity generation occurs within these wholesale electricity markets. Further, there are large regions of the country not currently served by an RTO—including many states in the West and, to a lesser extent, the Southeast—that have recently adopted some form of a coordinated energy market, even if not a full RTO, to harness at least some benefits associated with RTOs.

The core responsibilities of an RTO, which is a nonprofit entity, include running competitive markets, providing for the least-cost dispatch of electricity, ensuring open access to transmission for energy suppliers and purchasers, and maintaining transmission grid reliability. Members of RTOs include utilities, independent power producers, renewable energy developers, large end users (such as industrial customers), and, in some cases, environmental groups. Wholesale electricity markets match generators and electricity providers (such as distribution utilities), typically through bid-based markets. RTO rules governing wholesale market operations and transmission planning (and other issues) are regulated at the federal level by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). Both RTO and FERC decisions and actions may impact the deployment of clean energy and the ability of local governments to meet their clean energy goals, and there are opportunities for engagement at both levels.

RTOs are generally beneficial for clean energy deployment. Wholesale markets aim to promote competition among generators and equal access to transmission, allowing lower-cost generators to enter the market and guiding investment and retirement decisions for different electric-generating units. These markets have enabled innovative financing mechanisms that have helped drive the growth of renewables (e.g., virtual power purchase agreements, or vPPAs). Additionally, regional transmission planning conducted by RTOs, although in need of reforms, provides the framework for a transparent process for projecting future grid composition and determining transmission investment needs. Areas without an RTO do not enjoy the same level of competition, access, and transparency apparent in wholesale markets.

About This Paper

This working paper is intended as a primer for local governments interested in learning more about wholesale electricity markets and the issues affecting clean energy deployment. Specifically, it examines the effect that RTO policies, rules, and practices can have on the ability of local governments to achieve their clean energy goals. It provides background on the RTO-operated wholesale electricity markets, including their mission, how they operate, and their role in clean energy deployment. This paper then identifies issues related to transmission, market-specific rules, and the stakeholder process within these RTOs that may impede or support expanded clean energy deployment.

This paper is a companion to an earlier paper that explains how local governments can engage on wholesale electricity market issues (Ratz et al. 2021). By better understanding these markets and the factors impacting renewable energy within them, local governments can more effectively leverage their power—as both large consumers of electricity and as public entities representing their communities—to engage on areas that will have consequential impacts on achievement of their local goals.

Key Findings

The design of specific market rules and transmission processes and practices can either create barriers to or opportunities for clean energy deployment. Although RTOs demonstrate enabling features for renewable generation, substantive barriers exist because markets were primarily designed for more conventional fossil fuel and nuclear plants. Barriers are related to transmission, including rules and practices for transmission cost allocation, planning, and interconnection; market participation rules and determinations of resource adequacy; and governance.

Broader participation of stakeholders, including local governments, can benefit efforts to reform wholesale market policies that reflect outdated practices or incumbent interests. RTO decision-making is often heavily influenced by entrenched interests, including incumbent generators, many of whom own conventional resources, and may reflect outdated practices that keep uneconomic fossil fueled generation in the resource mix. RTOs may struggle to adopt regulatory and market structures that adequately reflect the value of renewable generation, hybrid resources (such as solar-plus-storage installations), and distributed energy resources, which are key resources for local governments looking to decarbonize.

By better understanding the barriers to clean energy within RTOs, local governments can strategically engage at the RTO or FERC level to advance their clean energy goals. A fundamental understanding of the most important issues affecting renewable energy deployment can enable local governments to target their engagement efforts toward specific areas that significantly impact their clean energy priorities. Priority market issues for local governments may depend on how they plan to achieve their goals and the types of projects they seek to implement, which can range from distributed generation to large-scale power purchase agreements (PPAs).

For deployment of large-scale renewables, transmission access and interconnection queues can be important issues that affect renewable energy project timelines and costs. Sufficient transmission capacity, shortcomings in transmission planning, and limitations in employing technologies that improve transmission system efficiency are all concerns in many regions, and solutions can take years to implement, which is a consideration for meeting long-term goals.

For local governments focused on distributed generation, developing plans to derive value from FERC Order No. 2222 represents a significant near-term opportunity. This can be important for local governments, particularly those looking for cost-effective community-wide clean energy solutions.

Local governments have a variety of engagement pathways available to them to effect change on wholesale market issues. In determining their engagement strategy, local governments should consider which issues are highest priority, what types of action might be most effective, their desired level of effort, and whether they want to engage independently or collaborate with peers.