Foreword by Amit Bouri

It has been my pleasure to know the World Resources Institute (WRI) since my earliest days in impact investing, even before I co-founded the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) in 2009. The World Resources Institute and the Global Impact Investing Network (the GIIN) have long shared a belief in the power of innovation to help build better systems for protecting the planet and its people.

Solving the generational challenges we face requires a hands-on approach from all of us. The United Nations created the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to provide us with a blueprint to overcome these challenges and build a more sustainable and inclusive world for all. Despite the clear targets laid out by the SDGs, the annual financing gap needed to meet them stands at approximately $4.2 trillion USD.

Yet, there are positive signals that funders—including grant funders and public and private investors—are committed to closing the gap. Today, the impact investing industry is valued at over $715 billion and is expected to continue to grow. At the GIIN, our goal is to ensure that all investments are made with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return.

It was only natural that when WRI invited the GIIN to support and co-author this report, Unlocking Early-Stage Financing for SDG Partnerships, we were honored to accept.

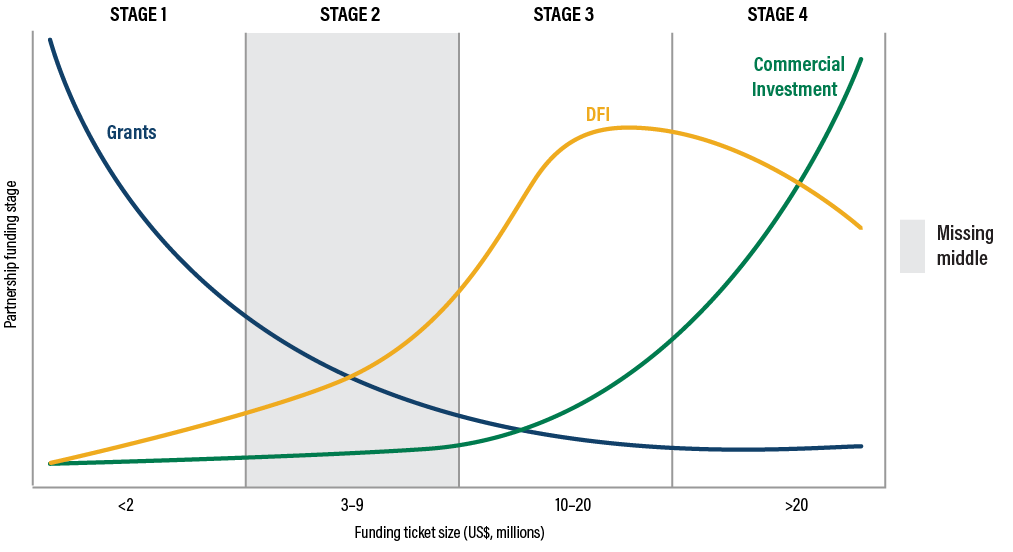

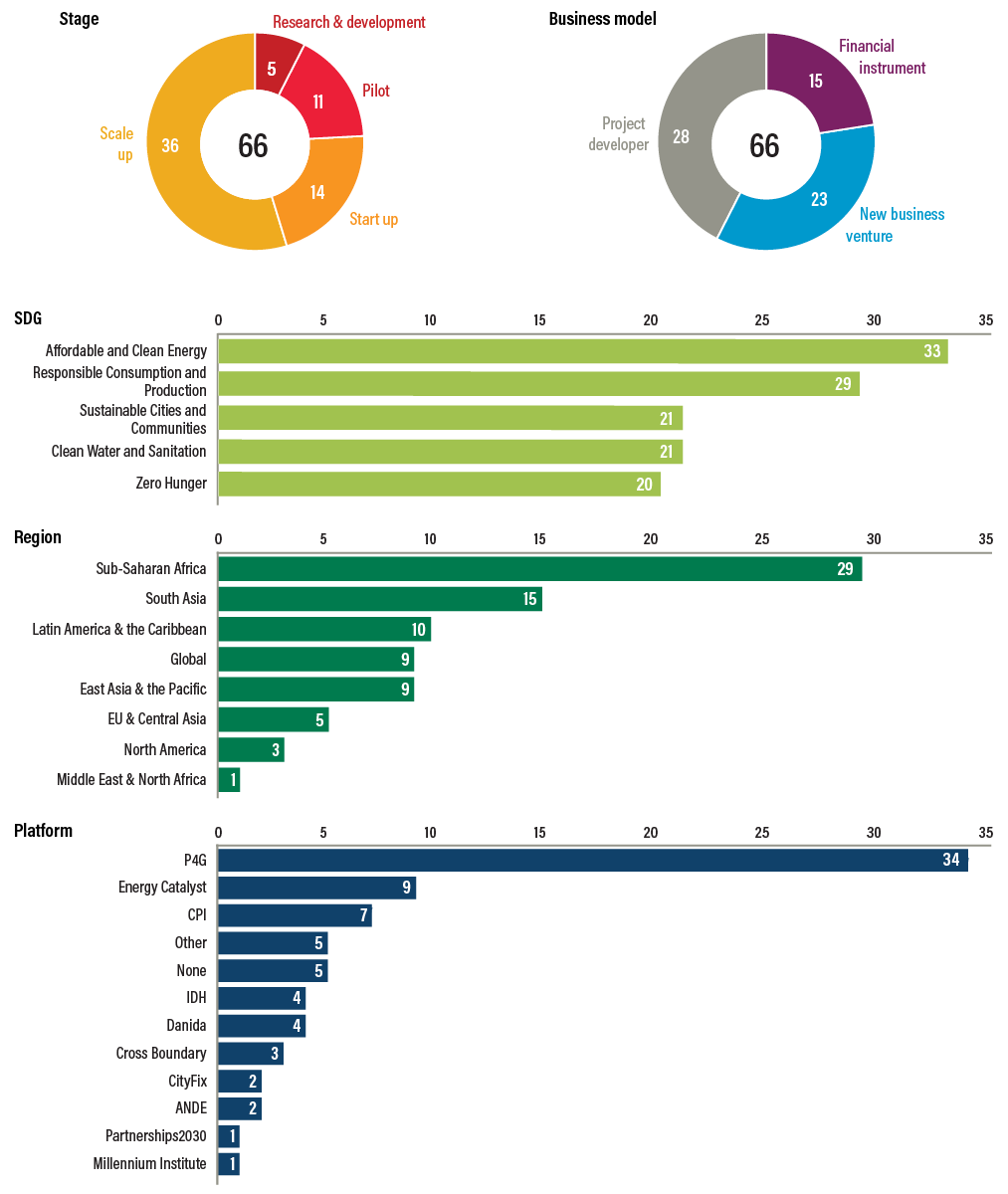

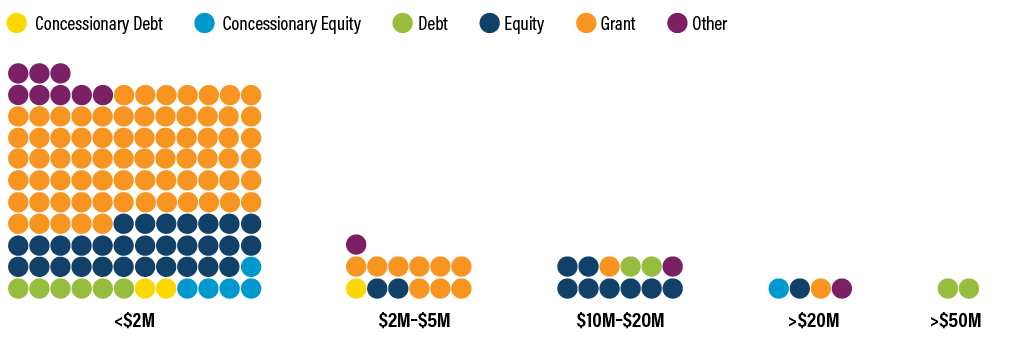

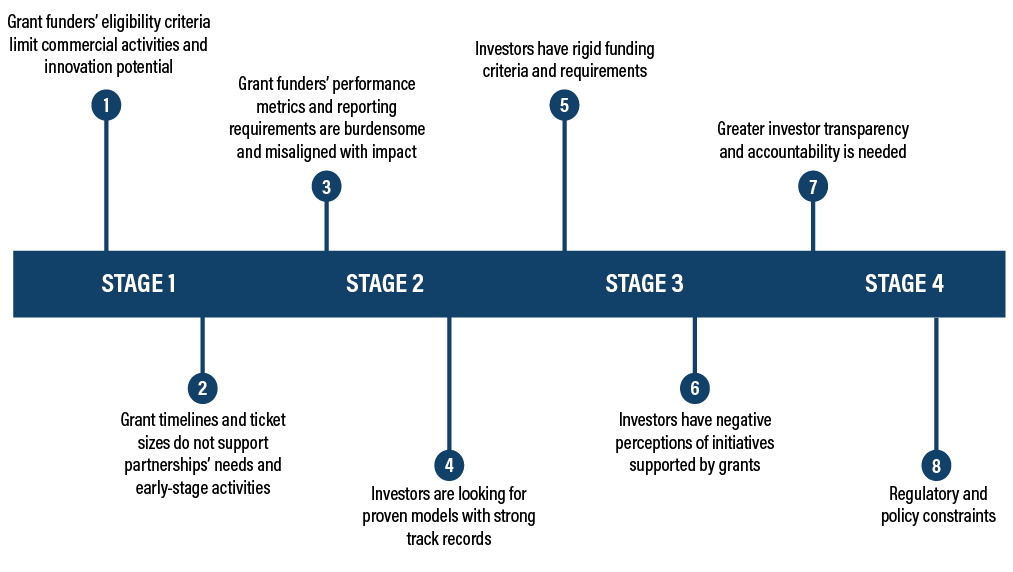

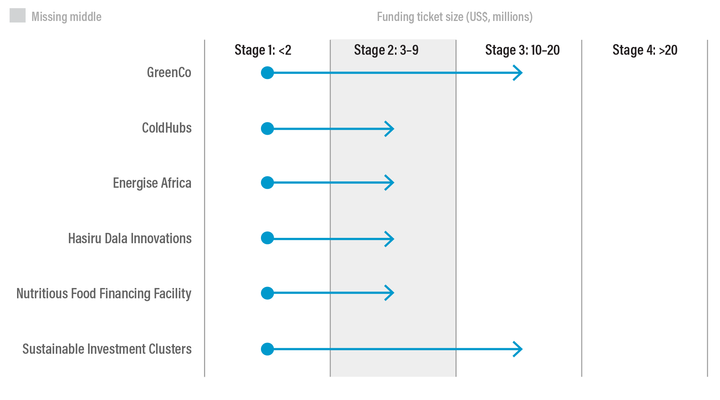

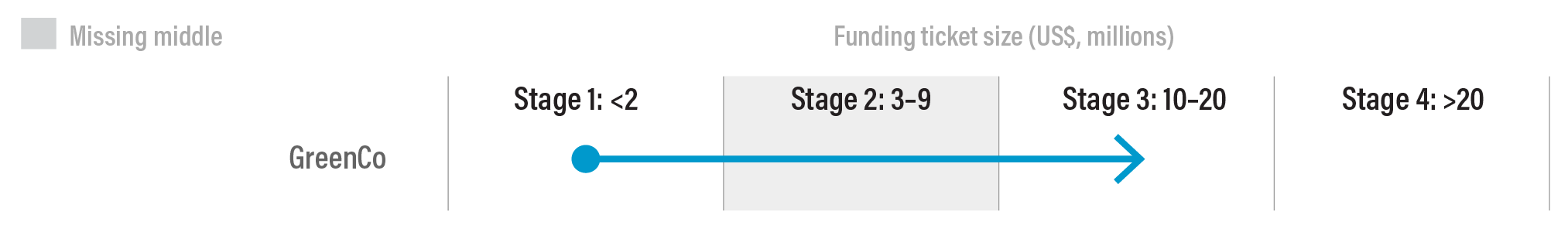

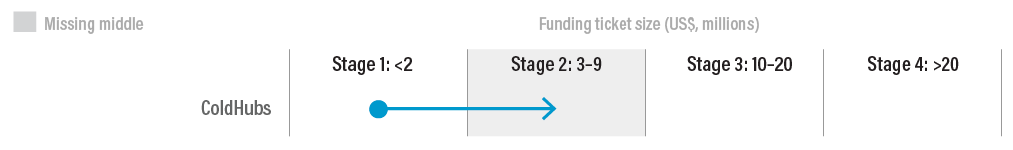

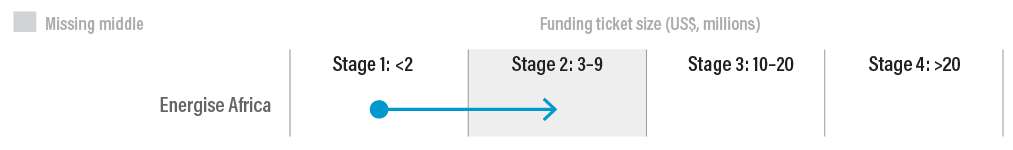

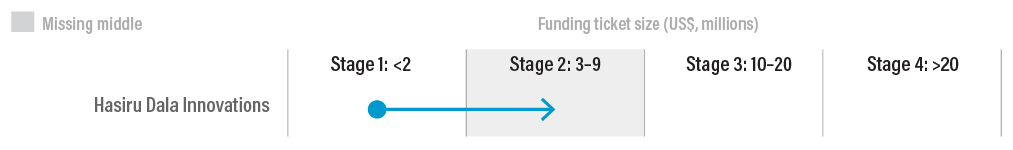

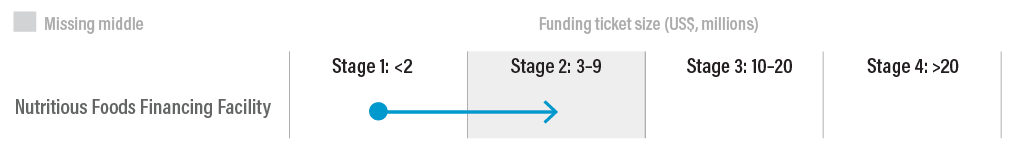

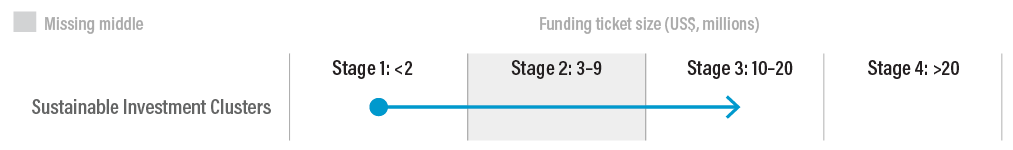

This report provides recommendations for how commercially driven partnerships and funders, particularly impact investors, working to advance SDGs can overcome the “missing middle.”

Readers of this report will learn from case studies highlighting six partnerships that have successfully overcome or are on their way to overcoming the missing middle. They will discover that while there is not a one-size-fits-all approach to successful partnerships, there are clear steps funders can take to improve the breadth and depth of the industry.

The WRI and the GIIN partnered on this report, so it’s no surprise that this report recommends funders align with each other on standard principles and impact measurement systems, and that they share data—positive and negative—on social and environmental performance as well as financial performance.

The report also outlines how we must be willing to explore and discuss lessons learned across the industry, regardless of the outcome. By identifying the roadblocks preventing us from addressing the SDG financing gap, this report shows us steps funders can take to ensure our world and its inhabitants are healthy for generations to come.

Because of funders’ willingness to share their stories for this report, we can provide meaningful recommendations. For that, we are incredibly grateful. Only through our collective learning and action can we achieve the vision of the world imagined by the SDGs.

Amit Bouri

Chief Executive Officer

GIIN

.png)