Foreword by Ban Ki-moon

On September 25, 2015, I had the distinct privilege to announce that all Member States of the United Nations had agreed to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) therein. These SDGs are a global call to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure the well-being of humanity. The nations of the world committed to achieve these goals by 2030.

I believed then, and even more now, that these goals can only be met through multilateral and multisectoral collaboration. This is why SDG 17, which calls for sustainable development through partnerships, is one of the most important of them all.

The rapid spread of the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates how interconnected we are through travel, trade, and communication. To end this pandemic, we need global cooperation and partnerships to treat the sick, develop the vaccine, and rebuild communities and economies damaged by this deadly virus. Like the pandemic, we know climate change threatens lives and livelihoods as warming temperatures lead to more frequent and severe storms, floods, wildfires, and droughts. The governments, businesses, and civil society organizations of the world must work together with great urgency to address these issues and all SDGs, such as ending poverty and hunger, expanding education and health care for all, increasing gender equality, and supporting sustainable and inclusive economic growth.

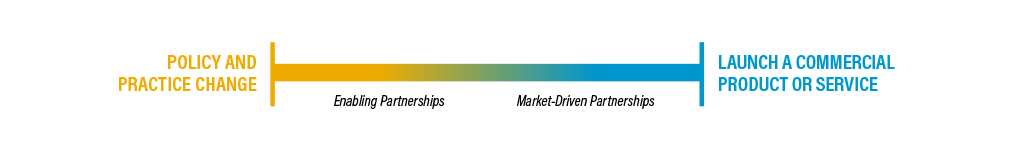

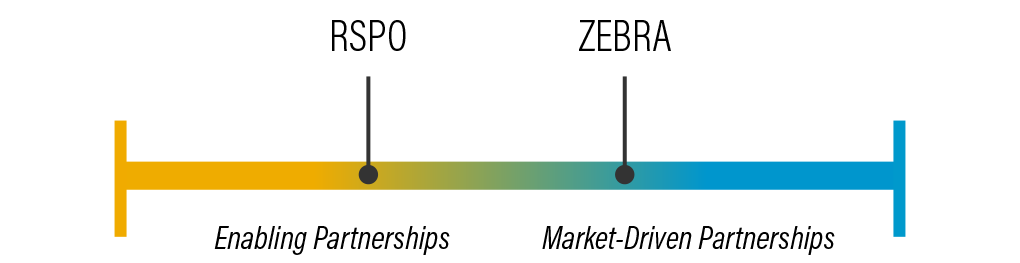

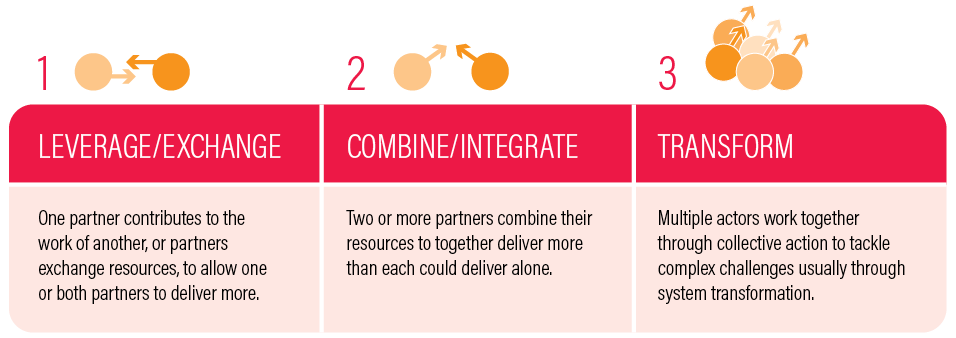

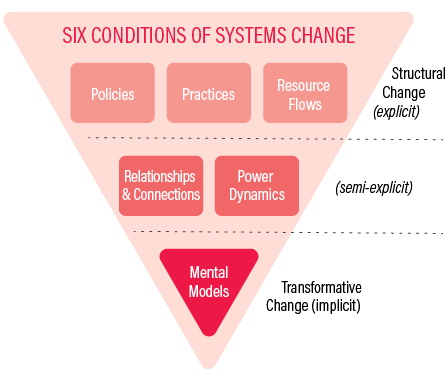

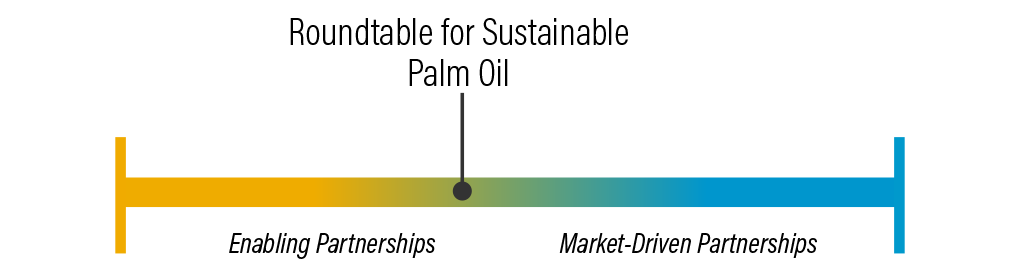

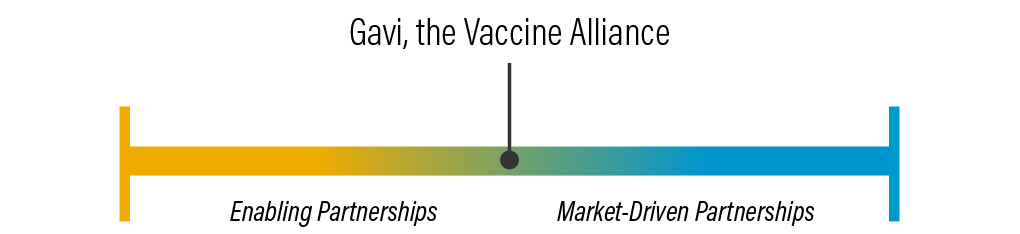

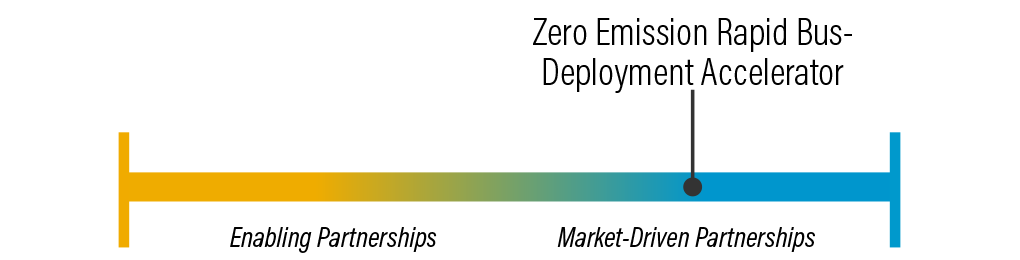

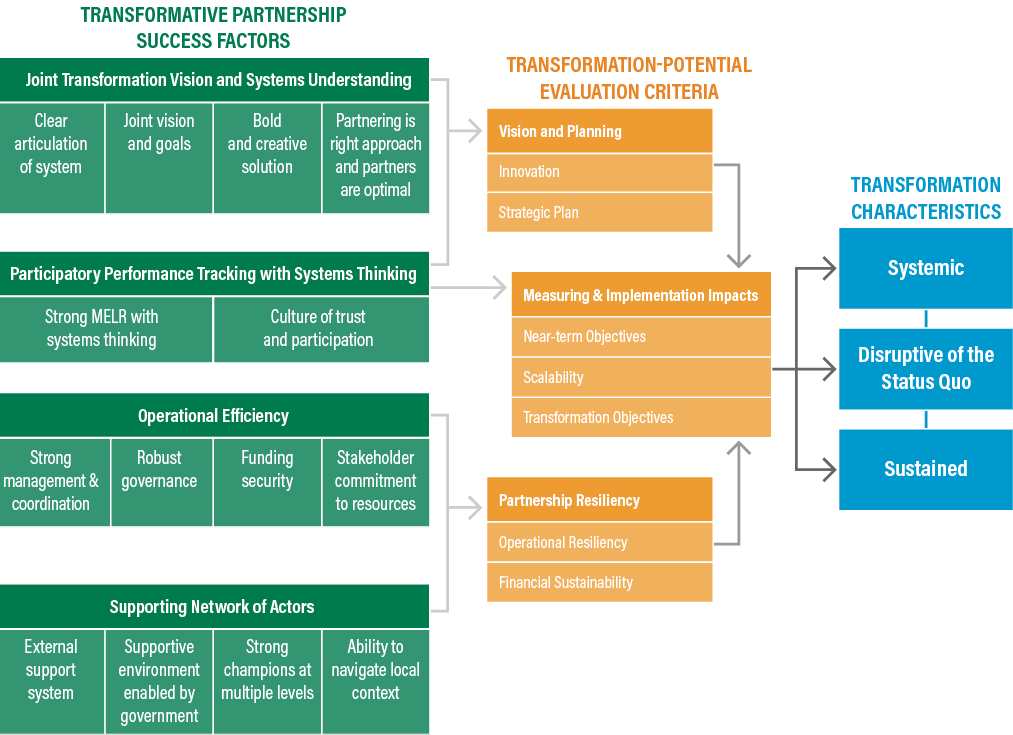

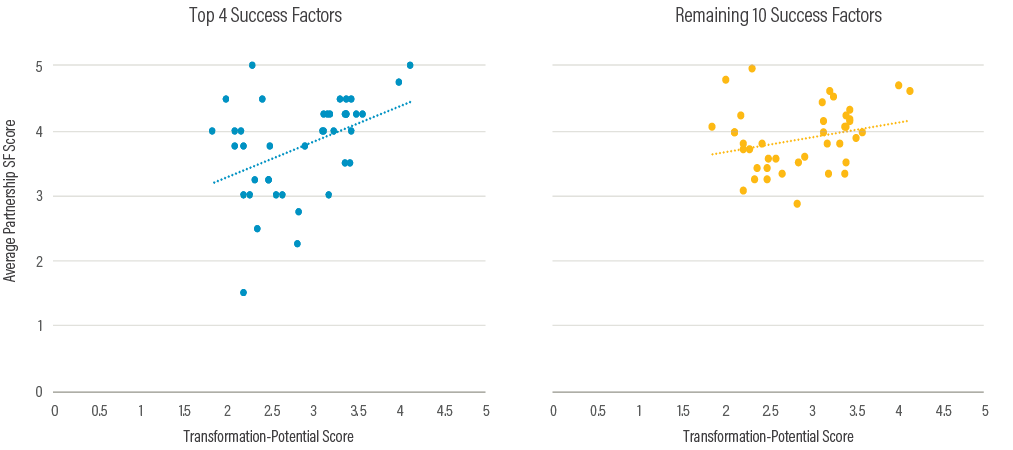

The Global Green Growth Institute is proud to collaborate with the World Resources Institute on this report, appropriately titled “A Time for Transformative Partnerships.” It details how partnerships can accelerate progress on the SDGs by better aligning the visions and designs to the main characteristics of transformative change, and it identifies the key success factors that are common among partnerships with transformation potential.

I encourage you to study this report and use this knowledge to embrace partnerships to achieve the SDGs. We need bold, decisive, and transformative action to ensure a sustainable future for all.

Ban Ki-moon

President and Chair of the Global Green Growth Institute

Eighth Secretary-General of the United Nations