Highlights

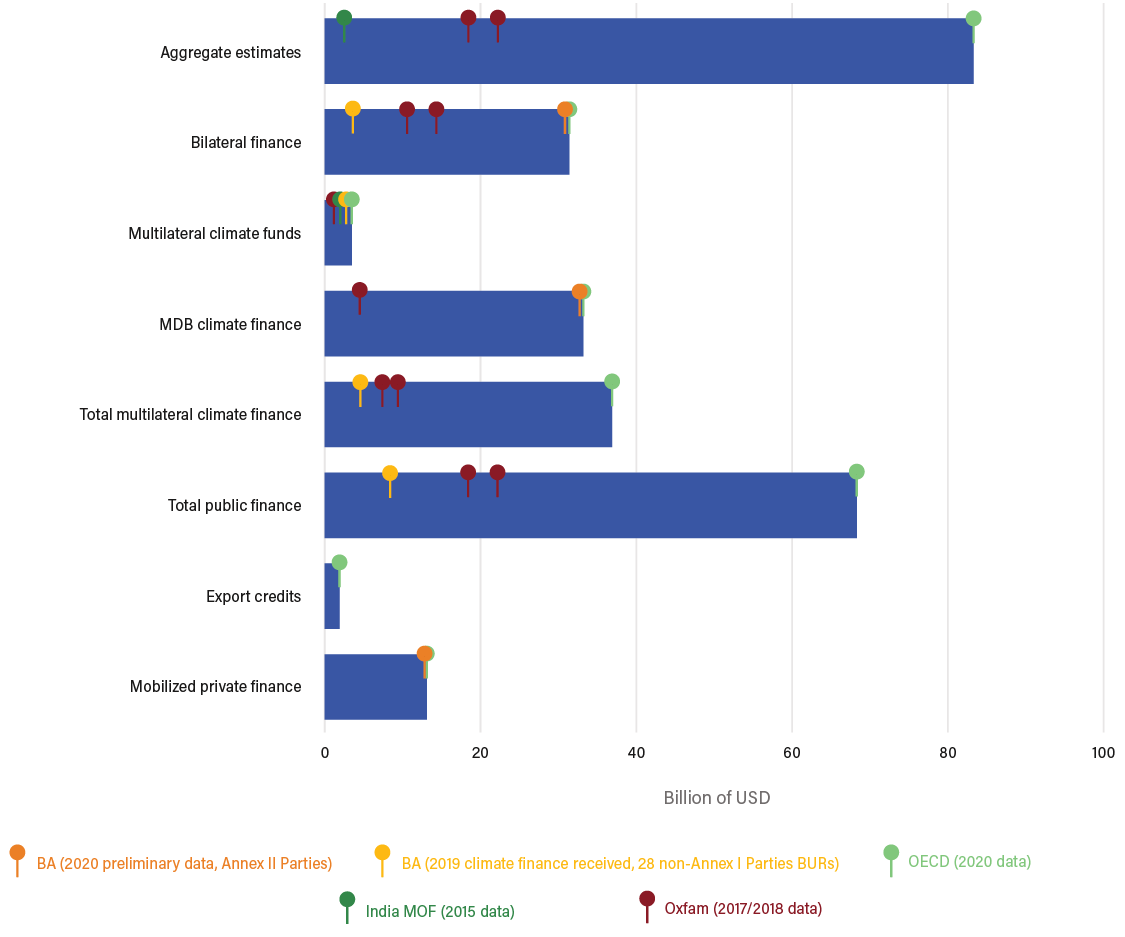

- In 2009, developed country Parties committed to jointly mobilizing US$100 billion per year by 2020 to address the needs of developing countries (UNFCCC 2009). The goal was formalized in 2010 and later extended through 2025 (UNFCCC 2010, 2015). As of September 2023, this goal had not yet been met.

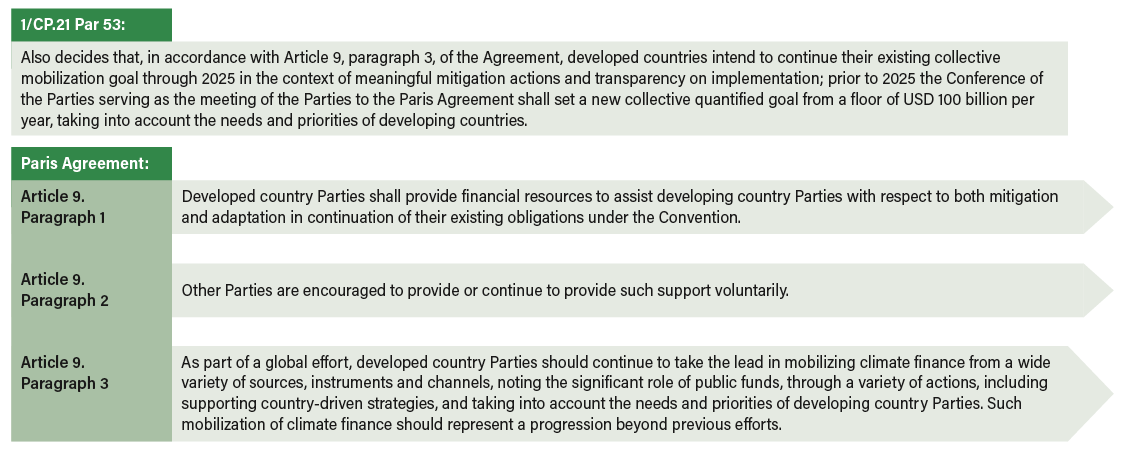

- In 2015, Parties at the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21), serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement (CMA), decided that they “shall set a new collective quantified goal (NCQG) from a floor of $100 billion per year, taking into account the needs and priorities of developing countries” (UNFCCC 2016). Deliberations on this new goal started at COP25 (2019), and since then deliberations have taken place through different processes, including submissions, technical expert dialogues (TEDs), and high-level ministerial dialogues (HLMDs) (UNFCCC 2022a).

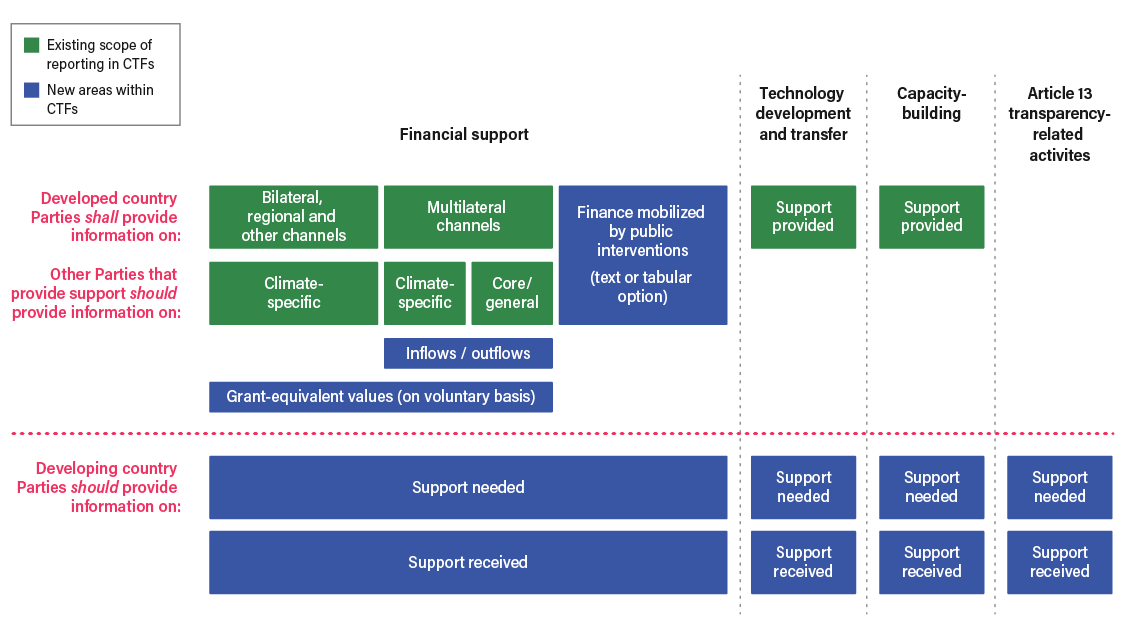

- This paper lays out a subset of some of the key negotiation topics concerning this new goal. These topics include the quantity of the goal, thematic scope, time frame, who should contribute, and transparency arrangements.