Executive Summary

Highlights

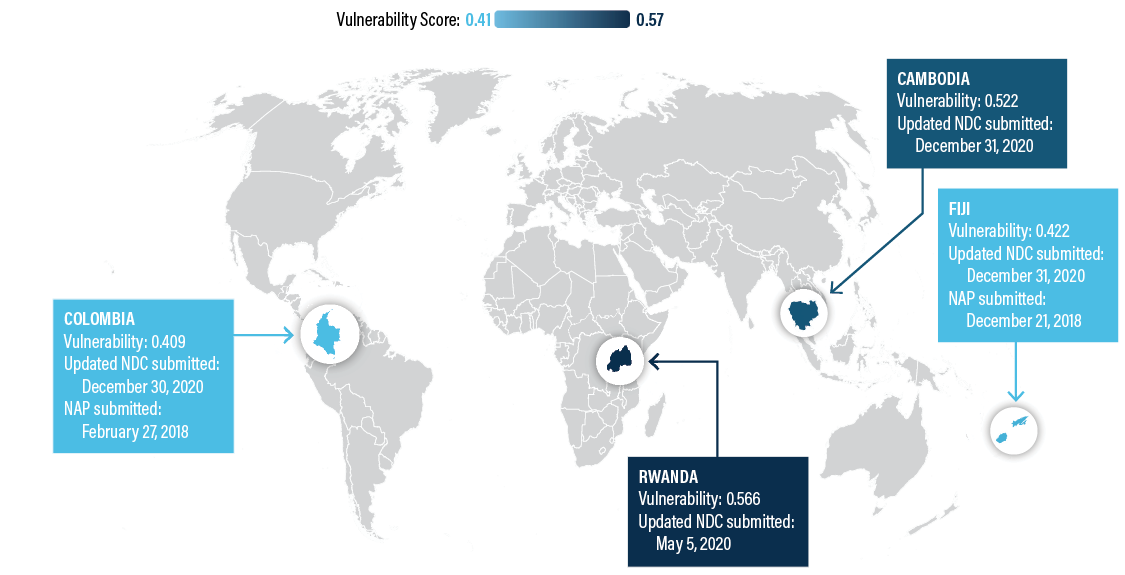

- This paper analyzes the processes used in four countries—Cambodia, Rwanda, Colombia, and Fiji—to develop the adaptation components of their updated nationally determined contributions (NDCs).

- The authors assess whether the following factors are evident in the NDC development process in each country: a whole-of-government approach, alignment with and integration of national and sectoral adaptation processes, use and strengthening of institutional arrangements, inclusion of the latest climate information, wide stakeholder participation, and focus on the needs of the most vulnerable.

- All four countries show improvement in the adaptation components of updated NDCs in terms of adaptation ambition and the process employed in their development. Six of the seven factors are evident across the four countries, with the exception of strengthened institutional processes.

- This assessment of NDC development and linkages to other planning processes for adaptation highlights good practices, which inform and strengthen future development of NDC adaptation components, as well as challenges for implementation.

- This paper presents the authors’ reflections to country governments, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), donors, and researchers to strengthen the process for developing the adaptation components of NDCs (adaptation NDCs) during each submission cycle, which will ultimately influence all countries’ climate resilience-building efforts.

Background: Adaptation in the NDCs

The adaptation NDCs are voluntary but are becoming an increasingly important part of countries’ commitments to the Paris Agreement. The NDCs were initially designed to communicate national greenhouse gas emissions abatement. However, many parties—particularly developing countries with high vulnerability to climate change—are communicating information related to adaptation needs and priorities, as well as past adaptation work, in their updated NDCs (Dixit et al. 2022).

Since adaptation NDCs are voluntary, countries are not yet using a standard template to develop them. Although the Paris Agreement provides guidance for an NDC’s mitigation components to improve clarity, transparency, and understanding and broader guidelines for separate instruments that may be applied to NDCs, such as Decision 9/CMA.1 for adaptation communications, no standard framework exists for adaptation NDCs. With gaps in existing guidance and agreed indicators, assessing the quality and collective ambition of adaptation NDCs remains challenging (Dixit et al. 2022).

Understanding the process by which countries develop their adaptation NDCs is critical for ensuring that it is strengthened at each update cycle. Assessing the existing process enables country governments to identify practices for robust adaptation NDC development, better align with other adaptation plans, and access financing for implementation. A better understanding of the process can also help national governments improve the clarity and quality of future submissions, and technical and financial packages can be tailored to support these.

About This Working Paper

This working paper presents an analysis of the process that four countries—Cambodia, Rwanda, Colombia, and Fiji—used to develop the adaptation components of their updated NDCs. Using an analytical framework for assessing adaptation ambition in NDCs developed by World Resources Institute (WRI; Dixit et al. 2022), the authors selected countries that had submitted updated NDCs to the UNFCCC by June 30, 2021, that had extensive adaptation components. The authors then examined the process behind NDC adaptation development in each country through stakeholder interviews, document review, and analysis of adaptation priorities using critical systems for adaptation identified in the Global Commission on Adaptation’s Adapt Now report (Bapna et al. 2019). The findings of this analysis highlight good practices as well as lessons for developing future adaptation NDCs. These findings will be useful to country governments, the UNFCCC, bilateral and multilateral donors, and researchers.

Case Study Country Selection and Analysis

The authors identified four countries with extensive adaptation NDCs using a qualitative framework to assess ambition in the WRI working paper “State of the Nationally Determined Contributions: Enhancing Adaptation Ambition” (Dixit et al. 2022). This framework helped identify adaptation NDCs that included prioritized actions, monitoring and evaluation (M&E), issues related to losses and damages, and transformative adaptation. Based on this analysis of adaptation NDC content, the authors selected Cambodia, Rwanda, Colombia, and Fiji to explore the NDC development process.

Using document analysis, literature reviews, and interviews with 17 experts and officials, the authors analyzed whether and how there was evidence for the following factors in each country’s NDC development process:1

- A whole-of-government approach where all climate-relevant sectors are engaged in the development of the adaptation component

- Alignment with national and subnational adaptation and development processes

- A high level of integration of adaptation in ongoing sectoral planning processes

- Use and strengthening of existing institutional arrangements for adaptation

- Inclusion of recent information on climate change impacts, risks, and vulnerabilities; for example, from latest national communications

- Wide stakeholder participation, including academia, relevant economic sectors, and diverse and vulnerable groups, during NDC development

- A focus on reducing vulnerability and issues related to gender, youth, and Indigenous peoples

Key Findings

Based on information available about the four countries’ experiences, Table ES-1 summarizes the analysis of the factors listed above. These findings are synthesized from a more detailed analysis included in Section 3.

Table ES-1 | Summary of factors in adaptation NDC development for four countries

Sources: a. Murphy 2018; personal communication between the authors and a United Nations Development Programme Climate Change Policy Specialist based in Cambodia, August 9, 2021; b. personal communication between the authors and an Environmental Consultant for the World Bank in Rwanda, August 27, 2021; c. Fiji, MoE 2020a; d. Fiji, MoE 2020a; e. Fiji, MoE 2021.

Reflections

For Country Governments

- National governments could help ensure that the process of updating the adaptation NDCs is adequately resourced and designed.

- The needs of the most vulnerable could be addressed through direct participation during development and by ensuring that local and provincial adaptation plans, which incorporate their voices, inform national prioritization.

- Formalizing the process of identifying adaptation priorities could help increase transparency and trust between different national stakeholders.

- Countries could consider creating robust and updated climate risk assessments at the country level for improved consistency in UNFCCC reporting and adaptation planning.

For the UNFCCC

- The UNFCCC could map out the information needs for different adaptation instruments under the Paris Agreement, such as the adaptation communication, the NAP process, the national communications, and the biennial transparency reports. Such a mapping could help countries avoid information duplication and clarify how to structure the adaptation NDCs to avoid overlap with other instruments.

- The Adaptation Committee could detail how its forthcoming guidance on adaptation communications may inform adaptation NDC development.

For Bilateral and Multilateral Donors

- Donors could increase their share of support for adaptation and support national governments to implement the adaptation priorities in the NDCs and NAPs, track their governance and implementation progress, and advance NDC implementation in critical sectors. As an important document that articulates country priorities, the adaptation NDCs could increase the profile of adaptation and help drive action.

- Developing countries also lack the resources to implement the adaptation priorities identified in the NDCs. Donors could increase adaptation financing and help national governments create and sustain resource mobilization plans or platforms as part of the planning process to catalyze and leverage funds for NDC implementation.

- Countries face barriers to monitoring the implementation of adaptation commitments. Donors could consider supporting the further development of M&E systems through governments and civil society to track implementation progress of the adaptation NDCs.