Executive Summary

Highlights

- Rural America can reap significant benefits from investments made in the new climate economy, including measures to advance clean energy systems, remediate abandoned fossil fuel production sites, restore trees to the landscape, and reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfire. Collectively, these actions can create new economic opportunities in rural places while addressing climate change.

- This working paper presents a detailed analysis of the rural economic impact of federal policies that invest in the new climate economy, including information about the geographic and sectoral distribution of those investments.

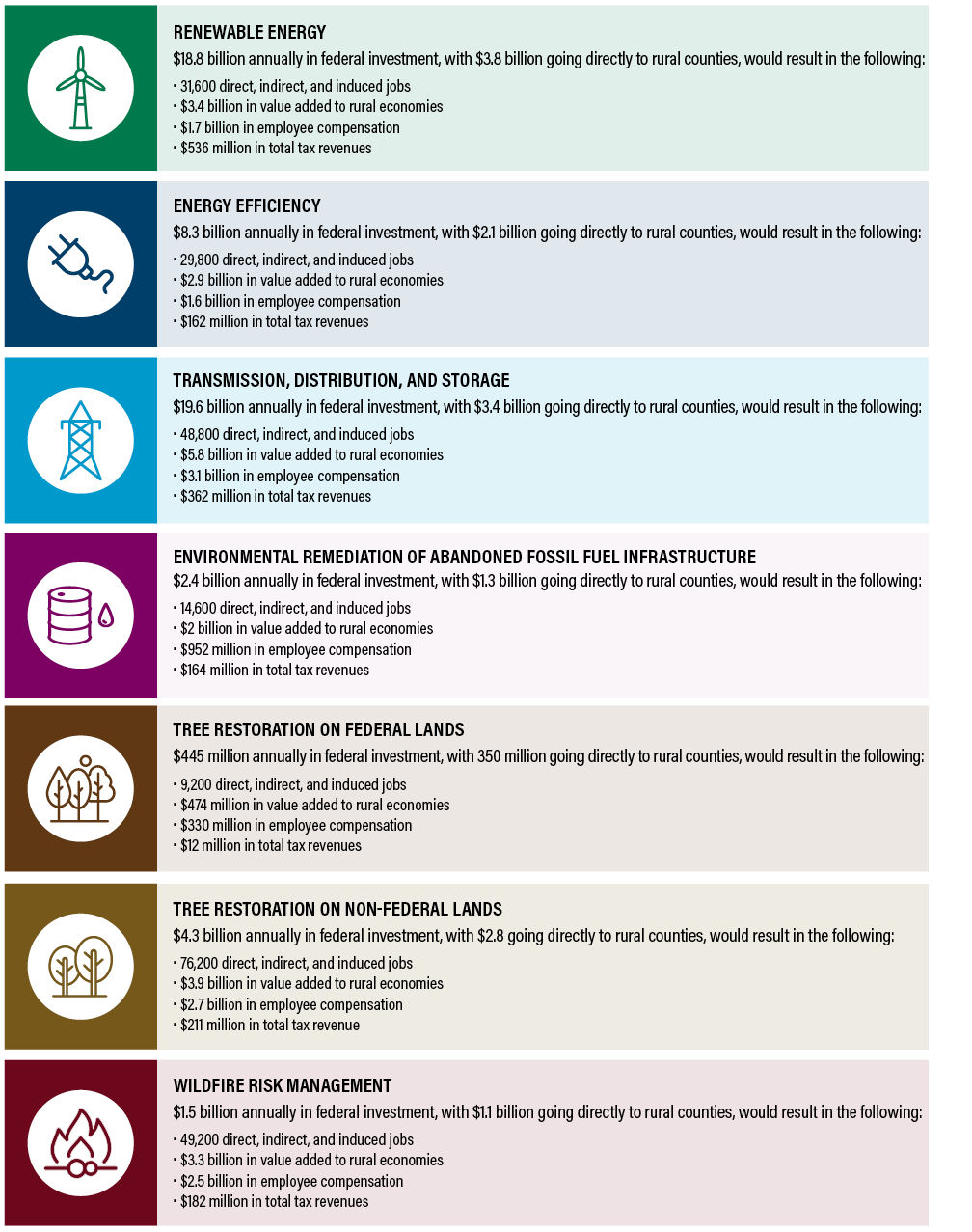

- The opportunities analyzed here would require US$55 billion in annual federal investment nationwide for five years, of which nearly $15 billion per year would flow to rural counties. This rural investment could support nearly 260,000 rural jobs that would last for five years (a total of 1.3 million job-years) across the country, if complementary measures were adopted to ensure that a minimum share of funding reaches rural counties. It would also generate $21.7 billion per year in overall value added to rural economies, including $12.9 billion in rural employee compensation and $1.6 billion in local, state, and federal tax revenues.

- Every $1 million invested through the new climate economy pathways included in this analysis would generate 17.5 jobs and $1.5 million in value added in rural economies.

- Nearly 45 percent of all rural jobs created by these federal investments would accrue to economically disadvantaged rural counties. Federal investments must specifically prioritize equity in distribution to ensure that these benefits reach rural communities in need.

Context

Rural America faces the dual challenges of lagging economic growth and increasingly severe impacts from climate change. These challenges have been highlighted by economic losses from the COVID-19 pandemic, which has exacerbated existing inequalities and infrastructure needs, alongside catastrophic wildfires and severe weather linked to climate change.

Addressing both challenges at once will require federal investment in building a new climate economy for rural America—one that reduces greenhouse gas emissions to net zero while creating jobs, uplifting economically disadvantaged communities, and enhancing ecosystem services. Prospective investments in the new climate economy have already garnered broad support from federal policymakers and rural voters alike, but strong federal policy has yet to be enacted. The current push by Congress and the Biden administration to invest in the country’s ailing infrastructure and tackle the climate crisis represents the most promising political moment in years to amplify the new climate economy in rural America.

Federal investment in the new climate economy can create jobs, bolster rural economies, and contribute significantly to addressing the climate crisis. Specific investment opportunities evaluated in this paper include the following:

- Developing renewable energy resources

- Making homes and industries more energy efficient

- Building infrastructure for clean energy transmission, distribution, and storage

- Cleaning up abandoned fossil fuel infrastructure

- Restoring trees on federal lands through reforestation and restocking degraded forests

- Restoring trees on private, state, and local lands through reforestation, restocking, and agroforestry systems

- Reducing the risk of catastrophic wildfire through prescribed burning and biomass removal

While not comprehensive, these opportunities are intended to be representative of key needs for investment in the new climate economy. They are the subject of analysis in this working paper.

About This Working Paper

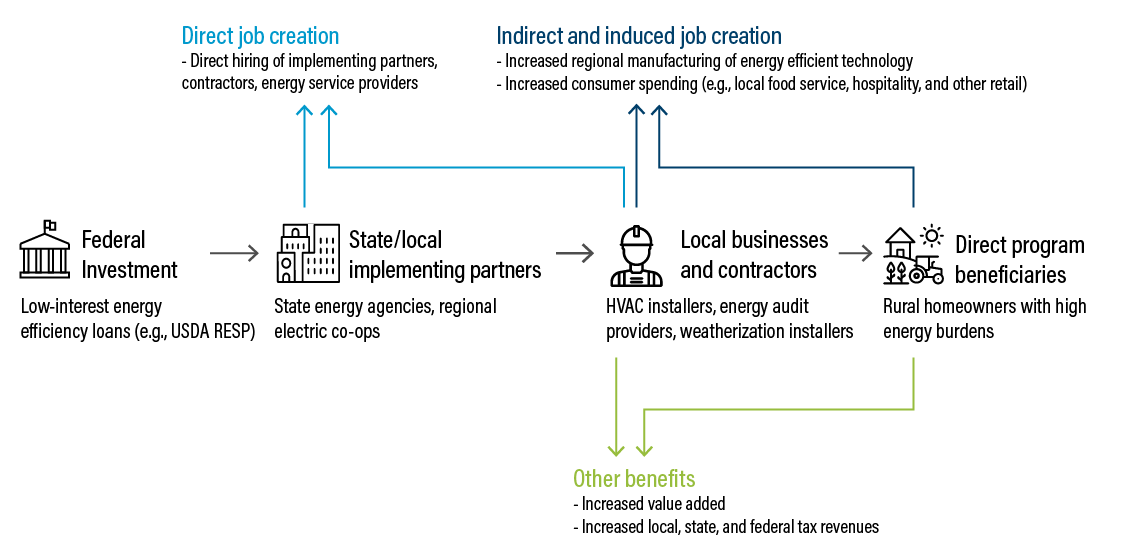

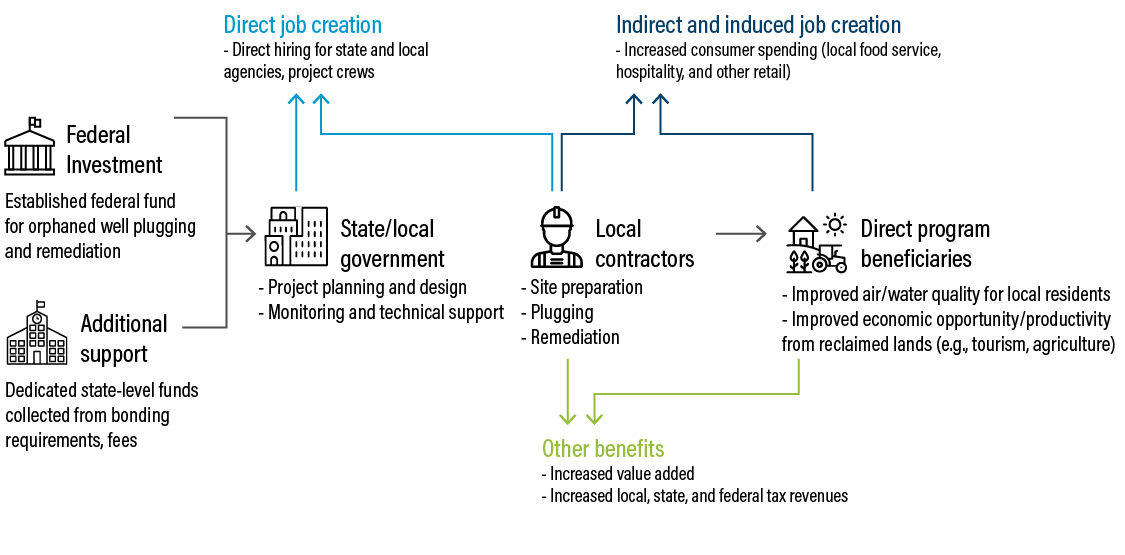

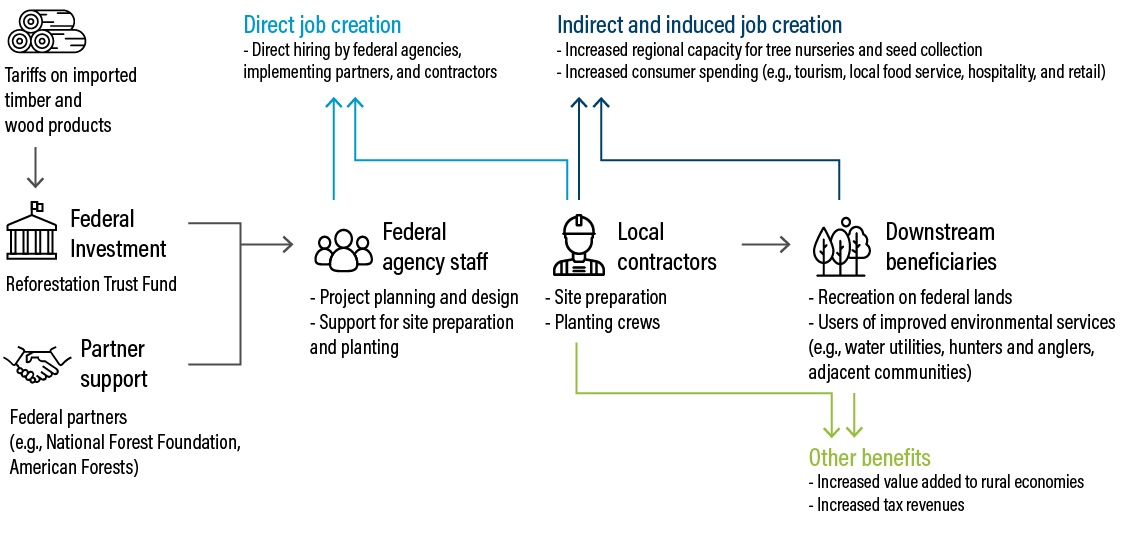

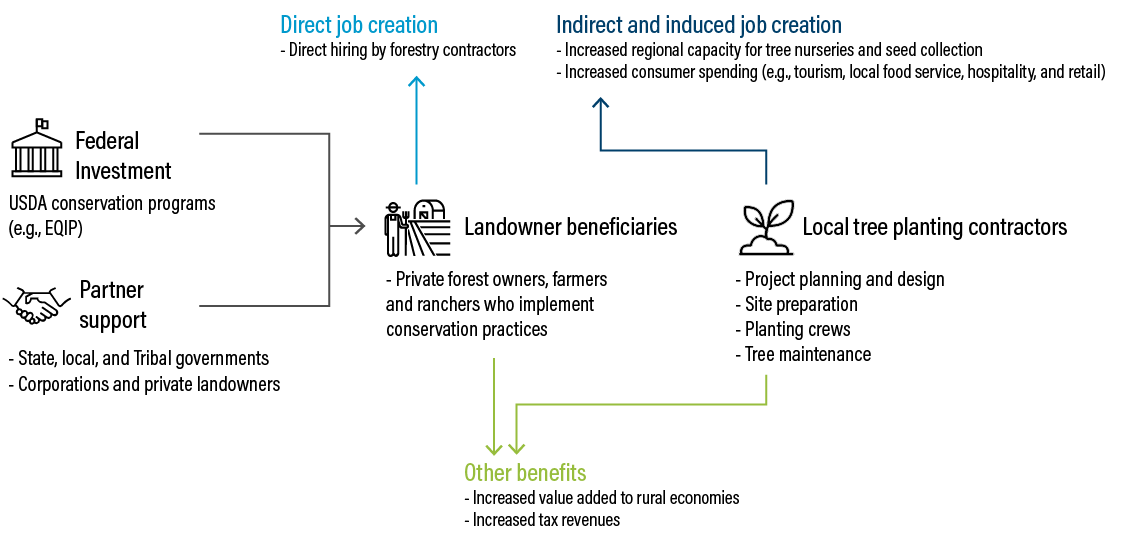

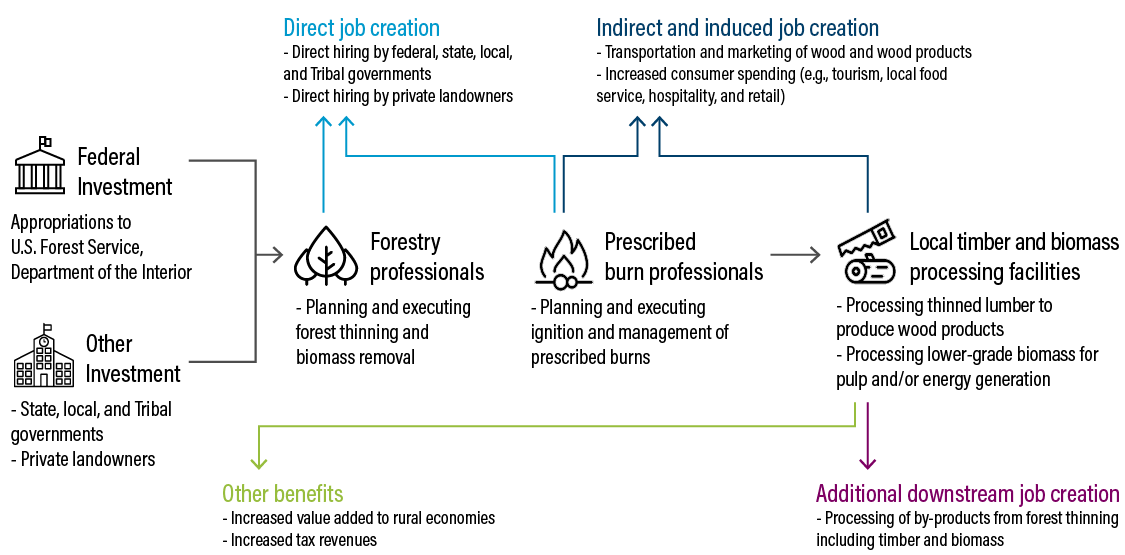

This working paper estimates the potential economic benefits in rural America from federal investments that support a new climate economy. Our assessment uses input-output modeling to estimate direct, indirect, and induced job creation in rural counties from specific federal investments across seven pathways, including opportunities in the energy and land sectors (Table ES-1). We also estimate the associated value added to rural economies, including total employee compensation and additional tax revenues to federal, state, and local governments. Based on these results, we analyze the distribution of rural economic benefits across the United States and the proportion of these benefits likely to accrue to economically disadvantaged rural communities, defined as counties identified as distressed and at risk by the Economic Innovation Group’s Distressed Communities Index.

We discuss federal policies that could catalyze investments in the new climate economy. The policies presented here could help rebuild U.S. infrastructure in a way that creates jobs, supports economically disadvantaged communities, and addresses climate impacts. While this discussion is targeted at federal lawmakers, state and local policymakers may also find value in these proposals.

Our analysis goes beyond most other published economic analyses of decarbonization policies by segmenting federal investment between rural and urban counties for specific opportunities in both the energy and land sectors, informed by interviews with practitioners and industry experts as well as qualitative case studies. The result is a detailed picture of how federal investments would be distributed across rural counties, including consideration of economically disadvantaged communities. This granularity reflects our understanding that good federal policy requires an intimate knowledge of how investments will translate into economic benefits across sectors and geographies.

This working paper is part of New Climate Economy, a project of the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, which seeks to enhance our global and national understanding of how climate policy can help unlock economic and social benefits. This paper estimates overall economic benefits only.

The Rural Economic Opportunity

We evaluate the impact of $55 billion per year in federal investment in seven areas of the new climate economy over five years. An estimated $14.9 billion of that investment would be directed to rural America. That investment would support nearly 260,000 direct, indirect, and induced jobs in rural counties for at least five years (a total of 1.3 million job-years) and 740,000 jobs in the country as a whole for at least five years (a total of 3.7 million job-years). This equates to 17.5 jobs created per $1 million invested in rural counties, compared with 13.5 jobs created per $1 million nationally.

This level of investment would also add $21.7 billion per year to rural economies for the first five years—$1.46 for every dollar invested. This includes $12.9 billion in employee compensation and $1.6 billion in federal, state, and local tax revenues. Table ES-1 shows the distribution of economic benefits across the seven investment areas in the new climate economy. In absolute terms, rural counties in California, Texas, New Mexico, Missouri, and Wyoming stand to gain the most in terms of job creation each year for the first five years (Figure ES-1).

Of the 260,000 rural jobs created by this investment, over 118,000—nearly 45 percent of all rural jobs—would accrue to economically disadvantaged rural counties. These counties would benefit from $9.8 billion added to their economies annually, including $5.9 billion in total employee compensation and $685 million in total taxes.

Figure ES-1 | Geographic Distribution of Rural Job Creation from Federal Investment in Seven Areas of the New Climate Economy

Source: WRI authors and BW Research.

Note: Delaware, the District of Columbia, New Jersey, and Rhode Island do not have any rural counties as defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The Policy Opportunity

The federal government has an opportunity to enact and expand policies that will drive investments in the new climate economy, creating jobs and bolstering rural economies in the process. Fully activating the opportunities analyzed in this paper would require a suite of federal policies, which could support a larger federal plan for rebuilding infrastructure and mitigating climate change. Policy opportunities for the new climate economy are shown in Table ES-2. They include policies that can positively impact the nation as a whole as well as policies specifically tailored to rural areas.

Table ES-2 | Federal Policy Opportunities by Investment Area

|

Renewable Energy |

|

|

Energy Efficiency |

|

|

Transmission, Distribution, and Storage |

|

|

Environmental Remediation of Abandoned Fossil Fuel Infrastructure |

|

|

Tree Restoration on Federal Lands |

|

|

Tree Restoration on Non-federal Lands |

|

|

Wildfire Risk Mitigation |

|