Foreword

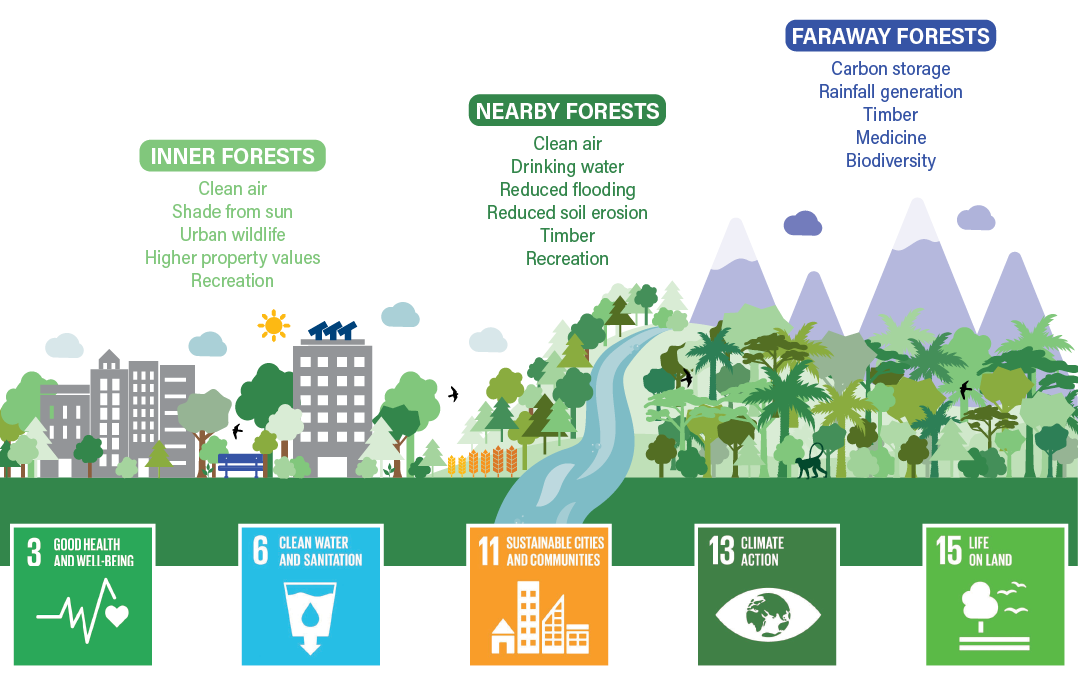

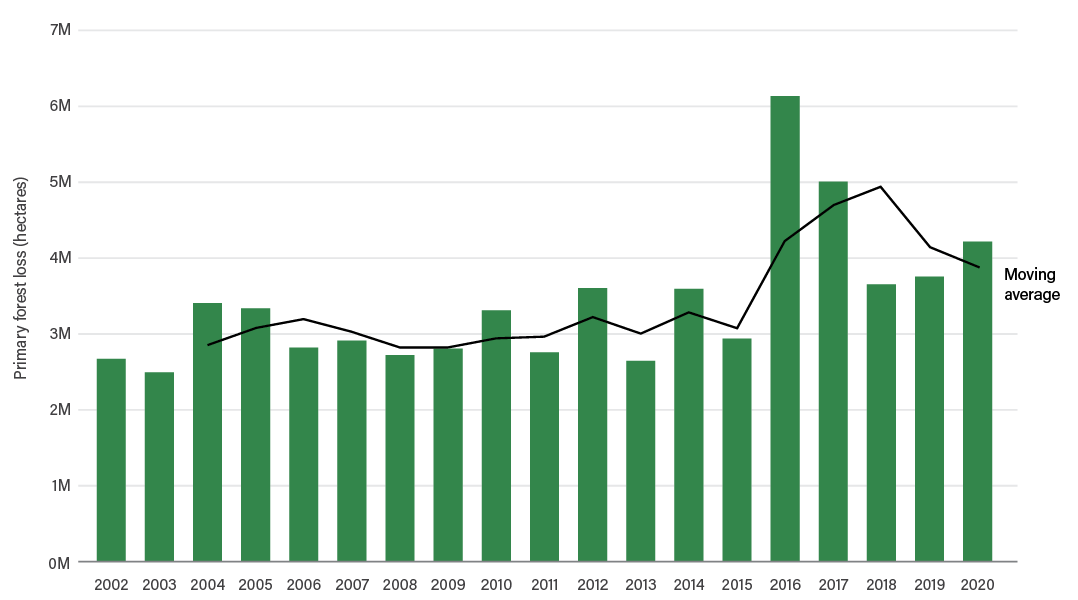

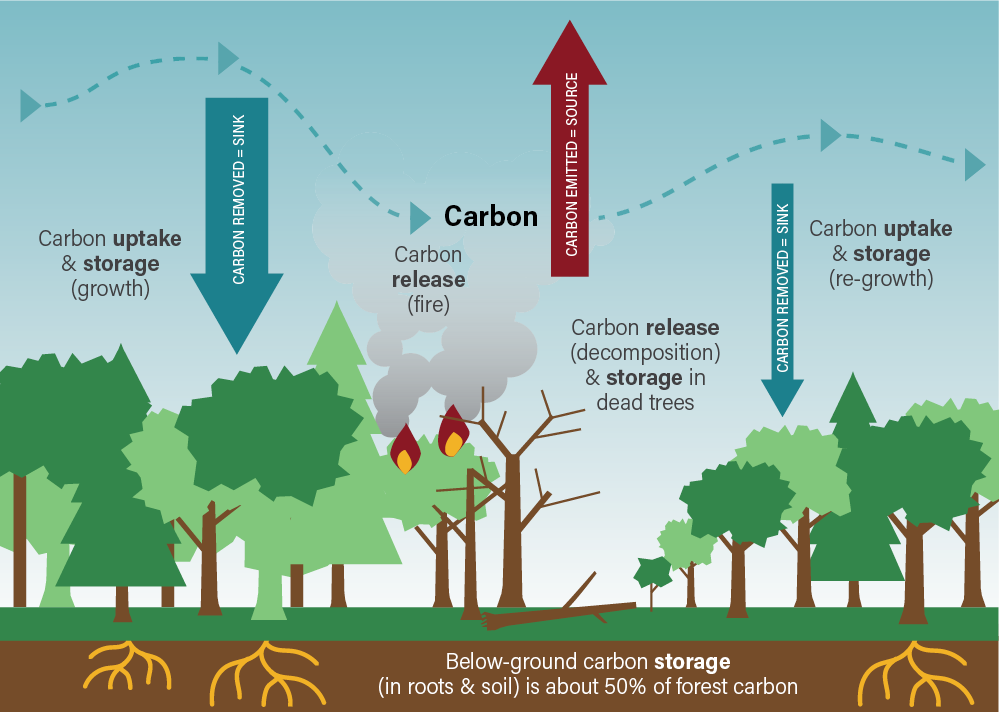

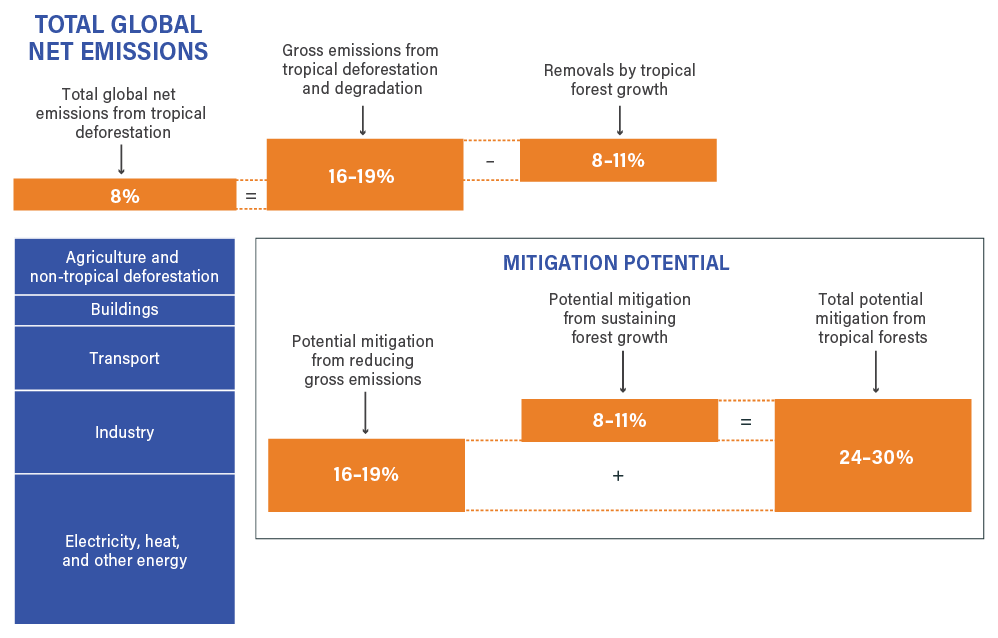

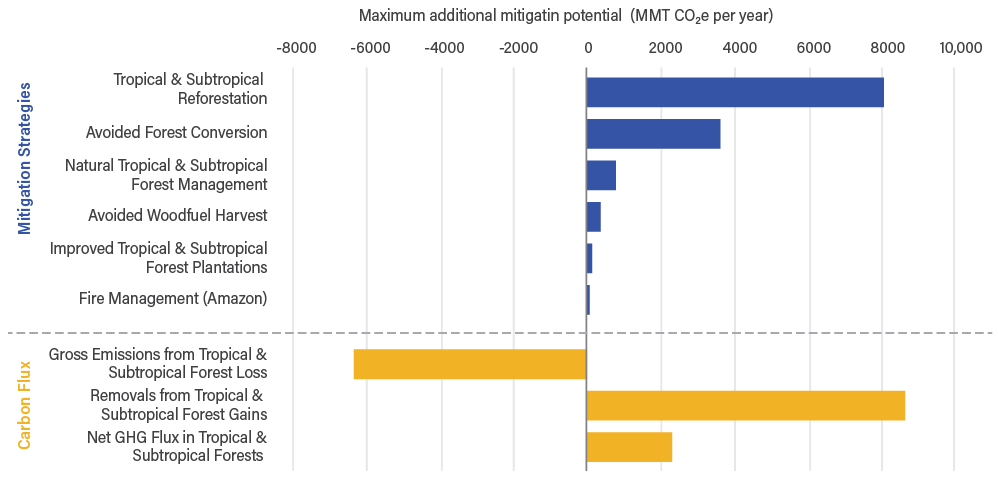

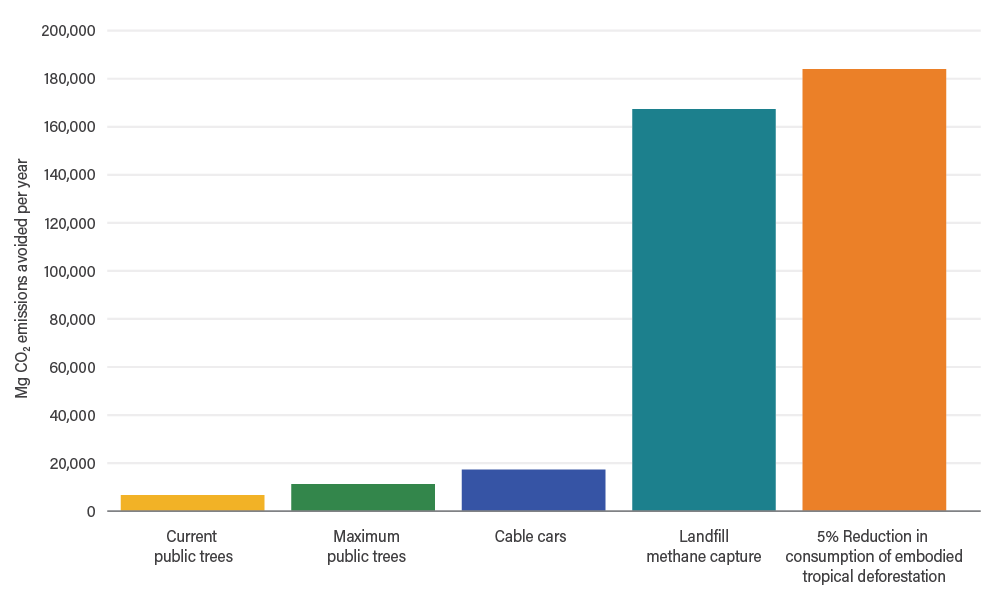

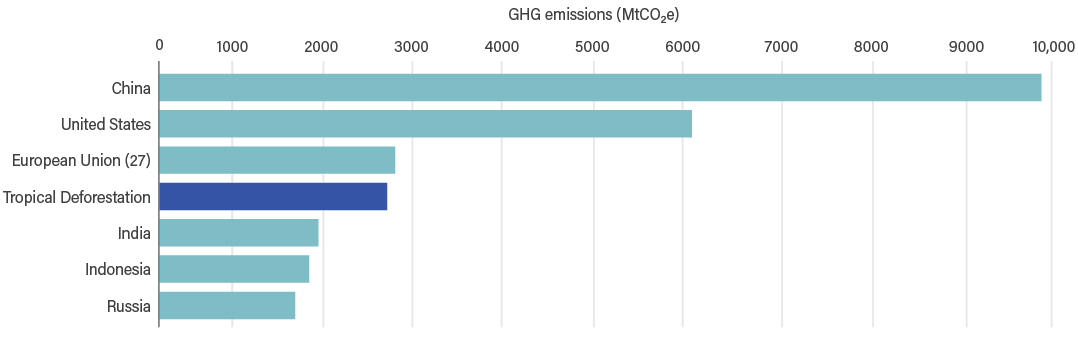

Cities across the world are reeling from the direct impacts of deforestation and forest degradation. In neighborhoods with low tree cover, higher mortality rates from extreme heat are on the rise, disproportionately affecting poor and marginalized communities. Meanwhile, deforestation and other disturbances to the world’s forests emit an average of 8.1 billion metric tonnes of carbon dioxide every year, contributing to devastating climate impacts in cities across the world.

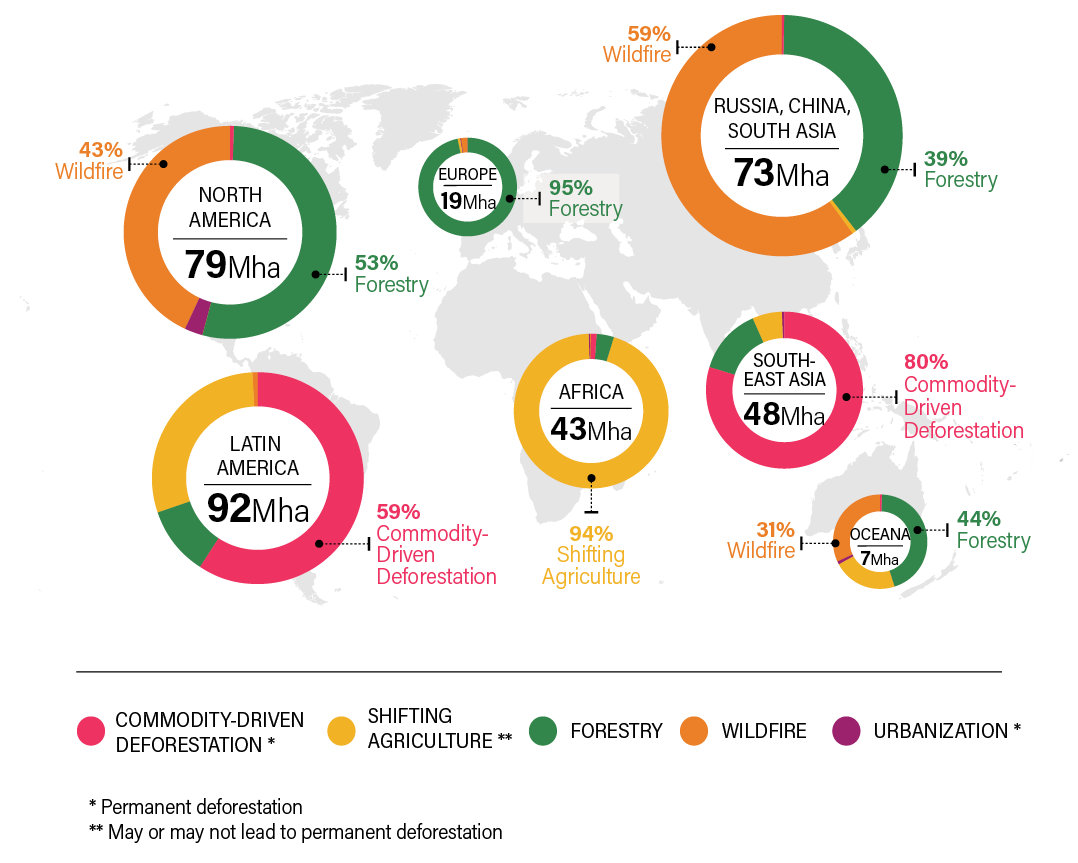

At the same time, cities are the ones shaping forests around the world. Although cities cover only a small proportion of the earth’s surface area, their carbon footprints are large and extend far beyond their limits. Ongoing consumption of globally traded agricultural commodities – the vast majority of which are consumed by urban residents – is the leading driver of tropical deforestation. For example, 80 percent of permanent deforestation in South-East Asia is the result of land conversion to grow commodities such as oil palm.

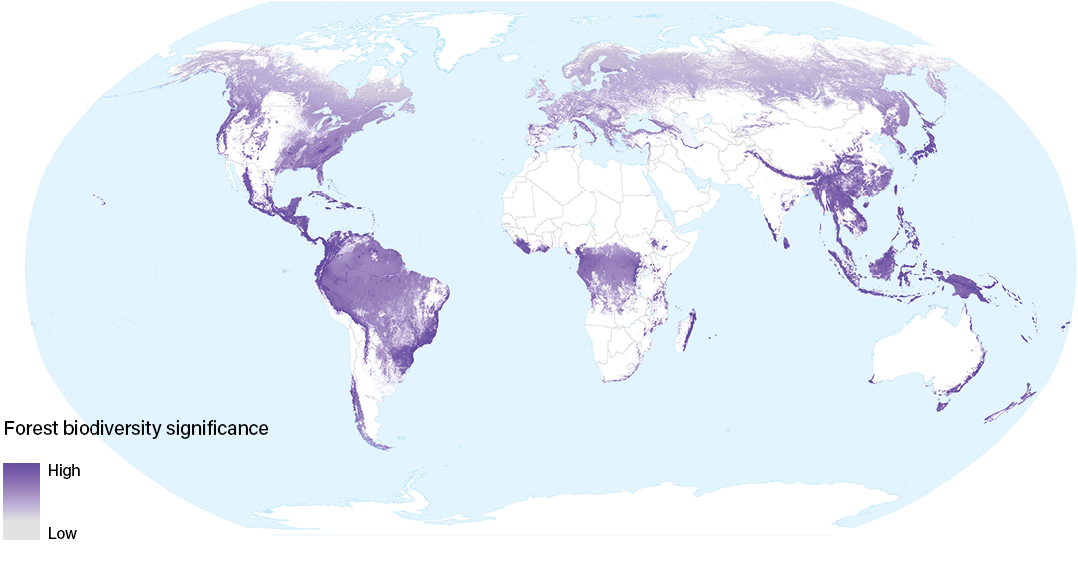

The fates of cities and forests are deeply intertwined—which also offers us an opportunity to change course. Cities can redefine the role of nature within and outside of their boundaries. By taking action to protect, restore and sustainably manage forests at all scales, cities can tackle the global climate and biodiversity crises while promoting the well-being of their residents. The public policies and procurement practices of cities have enormous potential to support the rejuvenation of the world’s forests—with huge benefits in return.

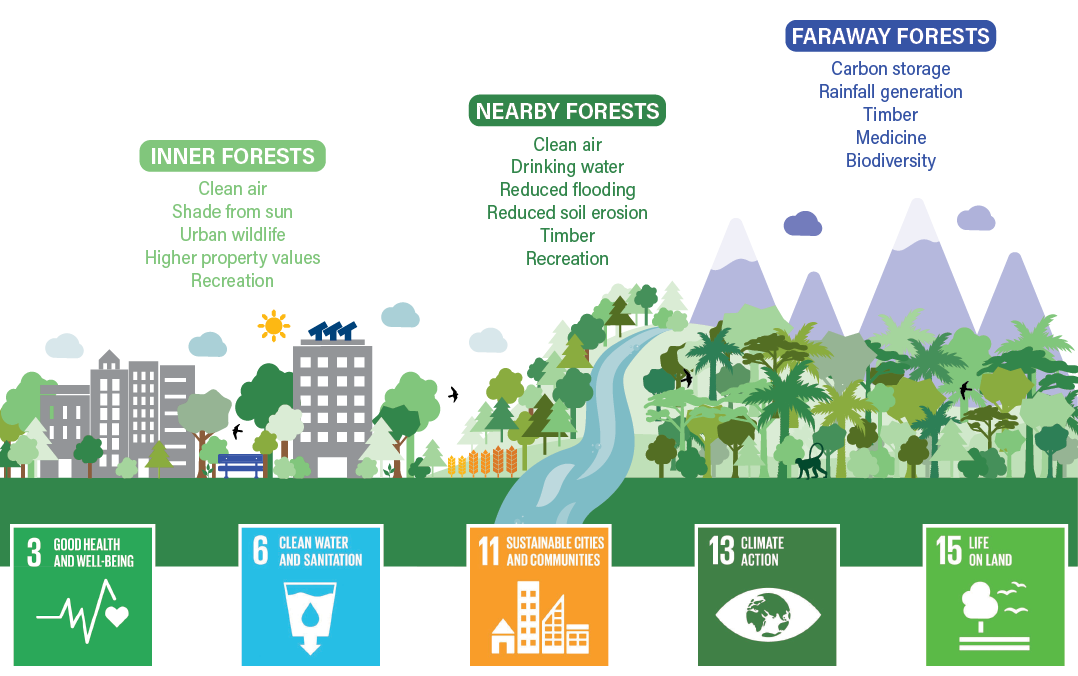

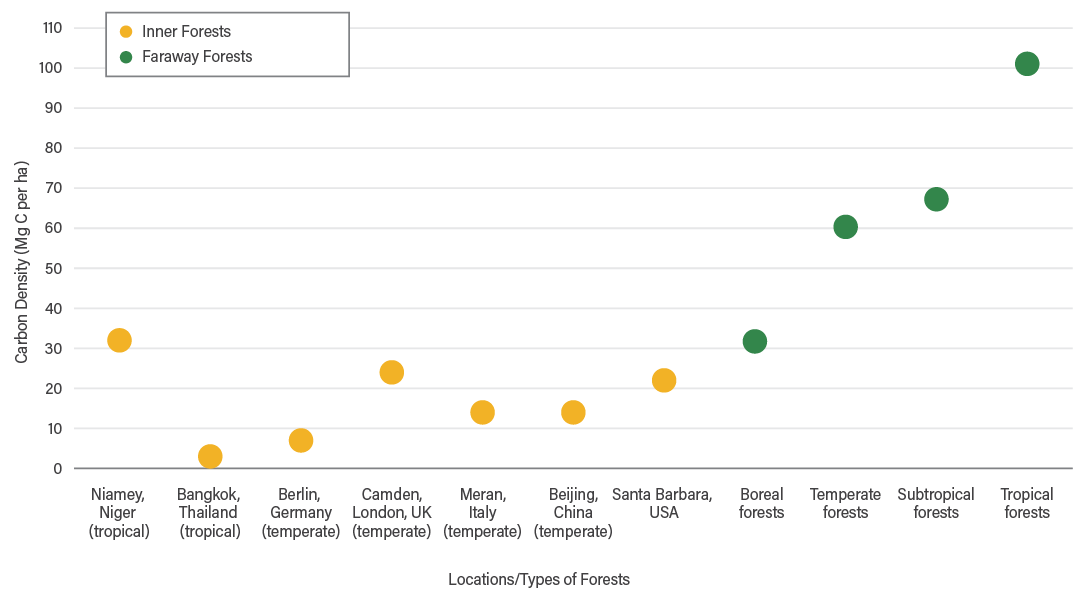

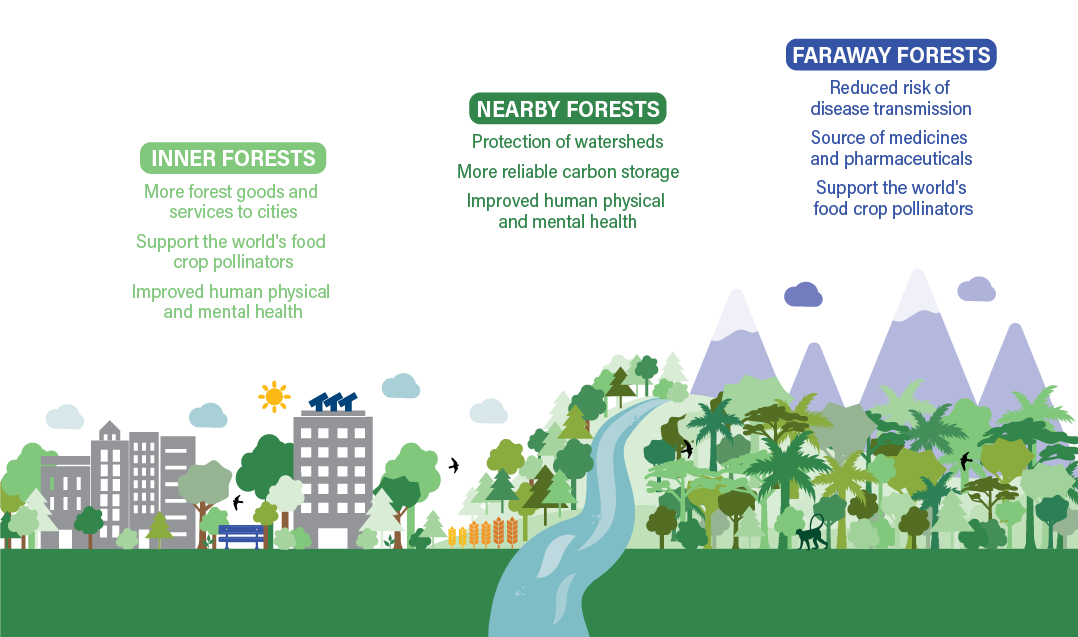

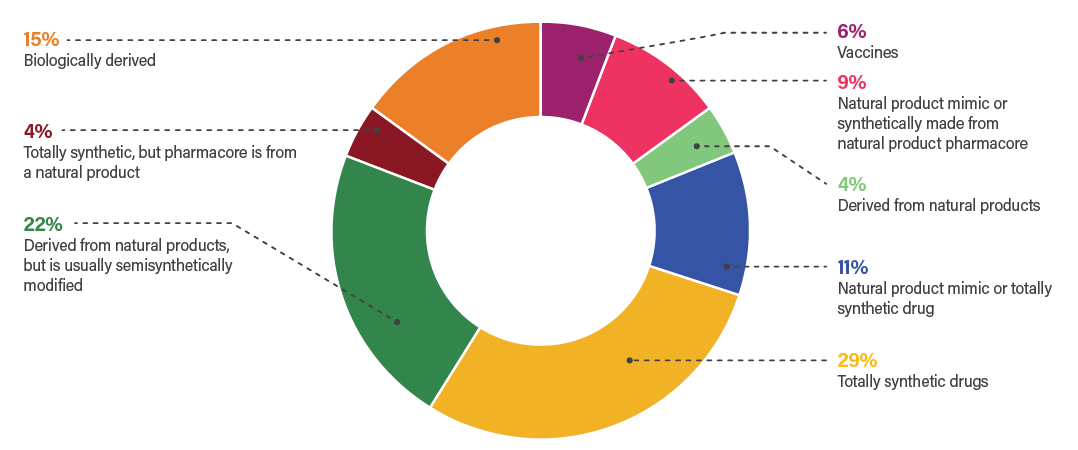

Until now, there has been a lack of clarity on how forests directly benefit cities and their residents. This report synthesizes hundreds of research articles to characterize the wealth of benefits that forests offer to cities in terms of human well-being, water security, climate mitigation, and biodiversity. The report evaluates the full range of benefits that cities receive from forests, whether they are inside, nearby, or far away from their boundaries, highlighting innovative examples from cities who are already leading the way. For example, the Green Cadaster in Skopje, North Macedonia offers a comprehensive map and catalog of every single tree and shrub in all public green zones within the city, making it easier for city officials to manage and track the benefits of green spaces. In Quito, Ecuador, a multi-stakeholder water fund known as FONAG has protected and restored over 40,000 hectares of forests with the support of over 400 local families. These are shining innovations and examples that decision makers across the world can learn from and seek to replicate in their own cities.

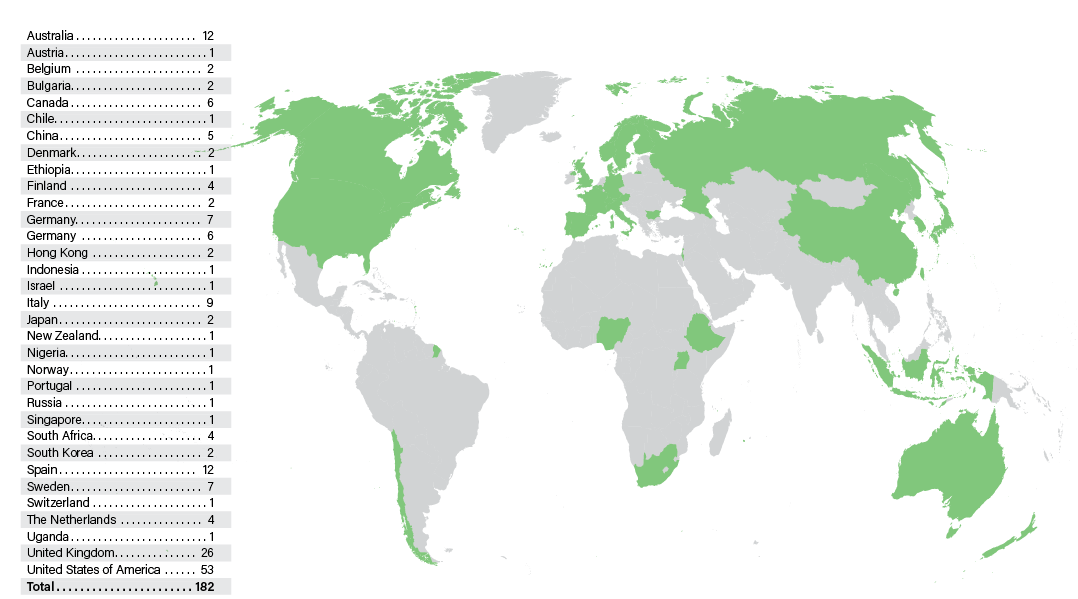

The report also echoes the Cities4Forests Call to Action on Forests and Climate that more than 50 mayors issued in 2021, calling for accelerated national and subnational action to support forests. As the first of its kind, this report provides city leaders with a new authoritative source to develop and expedite their efforts to protect forests worldwide.

As centers of political, economic, and cultural clout, city leaders have an increasingly important role to play. Mayoral voices are not yet tapped to their full potential in support of the world’s forests. This needs to change, and soon. After all, the battle on climate change will be won or lost in cities. We cannot afford to lose any more time. By 2050, an estimated 70 percent of the world’s population will live in cities. City leaders must act decisively in order to secure a green future for their growing populations and reap the benefits of a world with healthy forests.

.jpg)

Ani Dasgupta

President & CEO World Resources Institute