Executive Summary

Highlights

- Nature-based solutions (NBS) for adaptation can play a key role in managing the climate change crisis while yielding critical environmental, economic, and social benefits.

- Multi-stakeholder, multi-year, and multi-country initiatives centered on NBS have great potential to expand adaptation goals into their activities and reach more stakeholders.

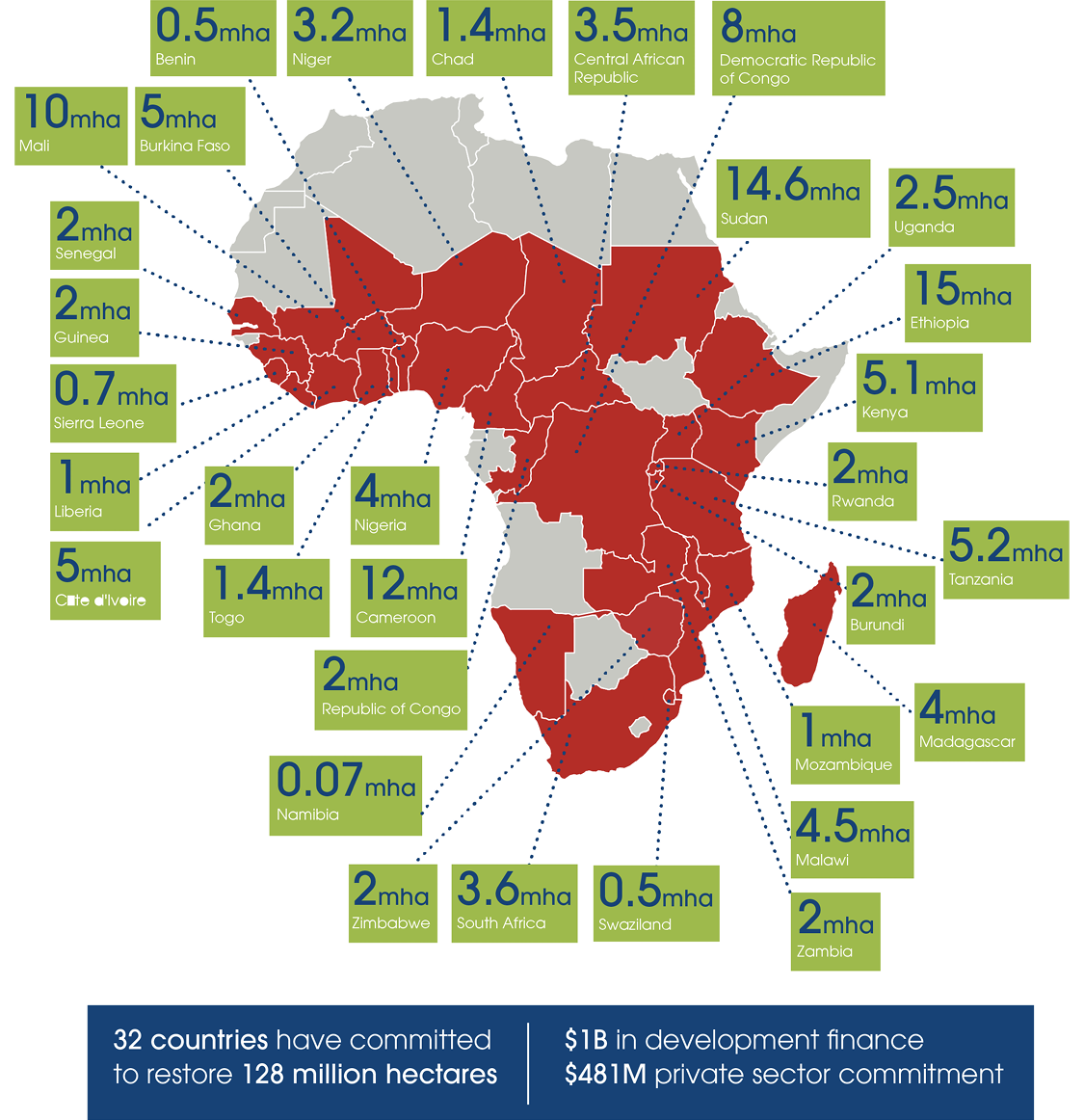

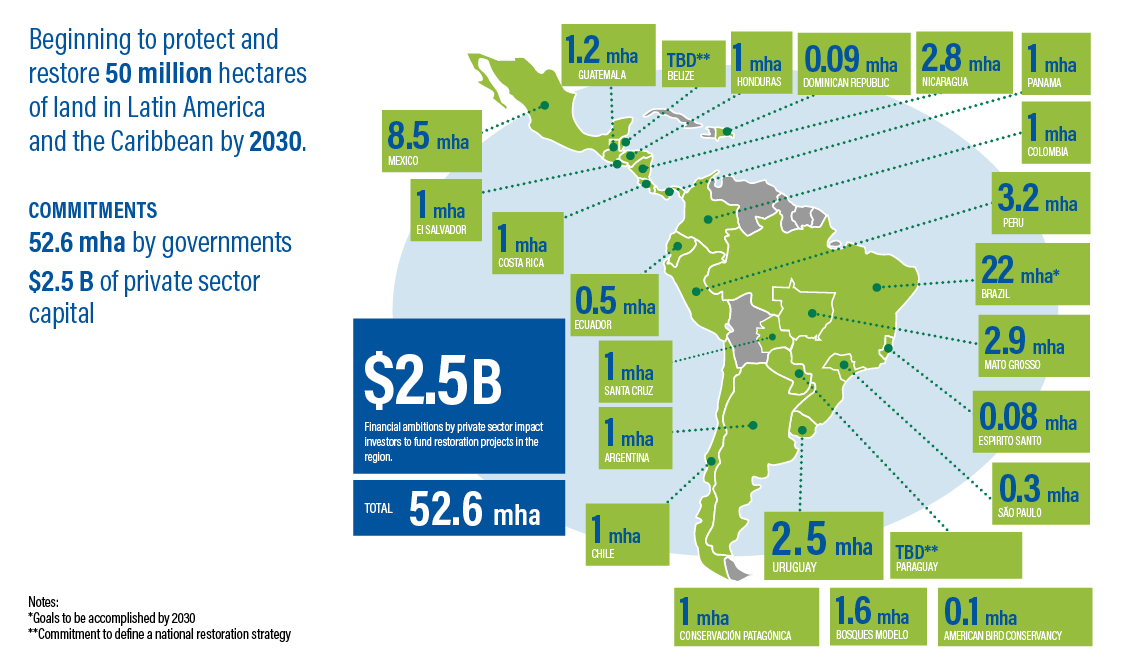

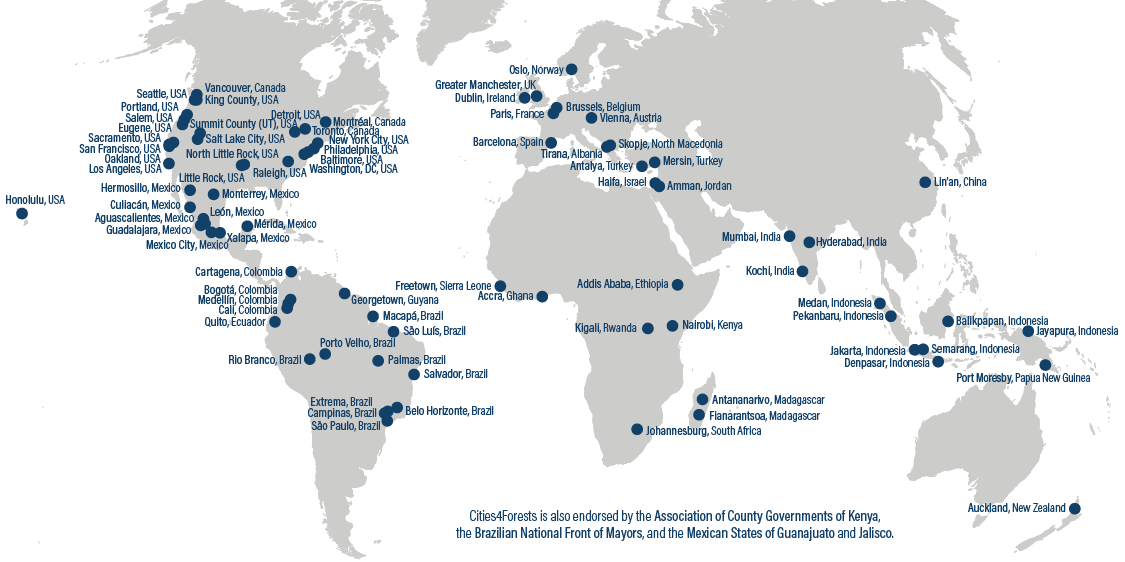

- This paper is based on a literature review, an online survey of 16 initiatives’ secretariat staffs, and follow-up interviews, with a deeper dive into three initiatives: the African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative (AFR100), Cities4Forests, and Initiative 20x20.

- Most of the NBS initiatives surveyed in this research were not designed with adaptation goals in mind yet 94 percent of staff surveyed indicated a high or moderate demand for and interest in adaptation. This paper identifies opportunities for them to integrate adaptation.

- Opportunities for NBS initiatives to address adaptation include better leveraging NBS initiatives’ comparative strengths to expand their adaptation activities; further facilitating finance and investment; and harnessing current political momentum to build the case for the effectiveness of NBS as an approach to adaptation.

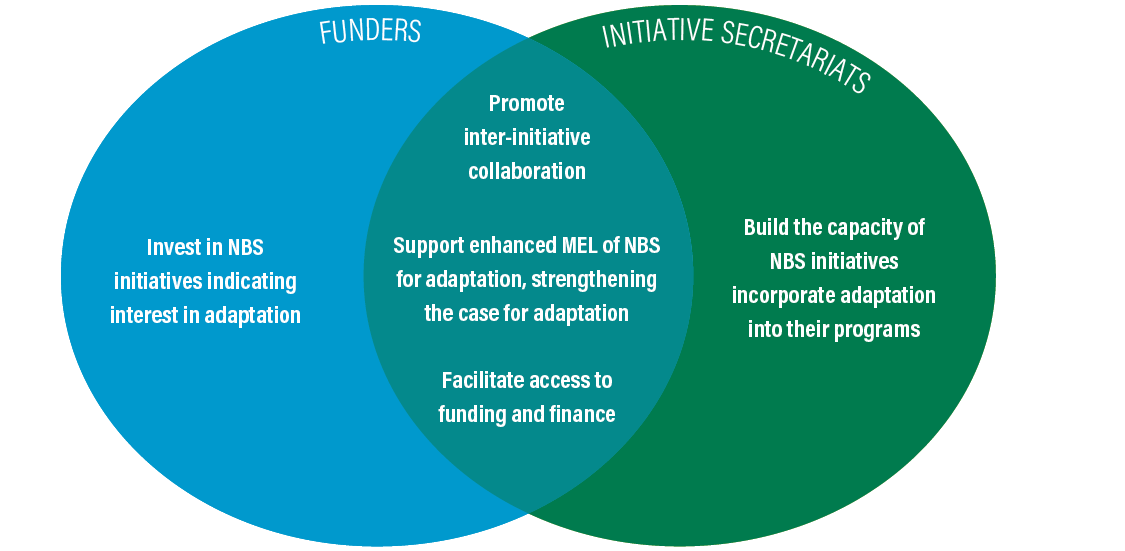

- Recommendations for funders and managers of initiatives include investing in expanding existing NBS initiatives to integrate adaptation by building their mandates, functionality, inter-initiative collaboration, and staff capacity on this topic.

What Are Nature-Based Solutions and Why Do They Matter?

The term nature-based solutions captures approaches to reverse natural resource degradation and biodiversity loss while promoting sustainable development. Across ecosystems, many NBS can also protect people and nature from climate impacts, including shorter-term hazards such as flooding and longer-term threats like desertification.

Reducing these risks is paramount, especially since they disproportionately affect vulnerable and marginalized groups (such as women, Indigenous peoples, the elderly, people living in poverty, and those with disabilities) who are directly dependent on natural resources for their livelihoods and/or are physically exposed to climate impacts. These groups stand to benefit the most from nature-based climate adaptation solutions, revealing an important opportunity to advance equity outcomes. Additionally, evidence continues to emerge showing that an NBS approach can be more effective and result in greater savings, social benefits, and avoided losses than business-as-usual interventions (World Bank 2020; Chausson et al. 2020).

The links between ecosystems and societal resilience are clear. When ecosystems degrade, communities become more vulnerable to climate risks and lose vital resources provided by nature. NBS approaches can protect livelihoods and human well-being, and help societies better adapt to the changing climate.

Key Findings

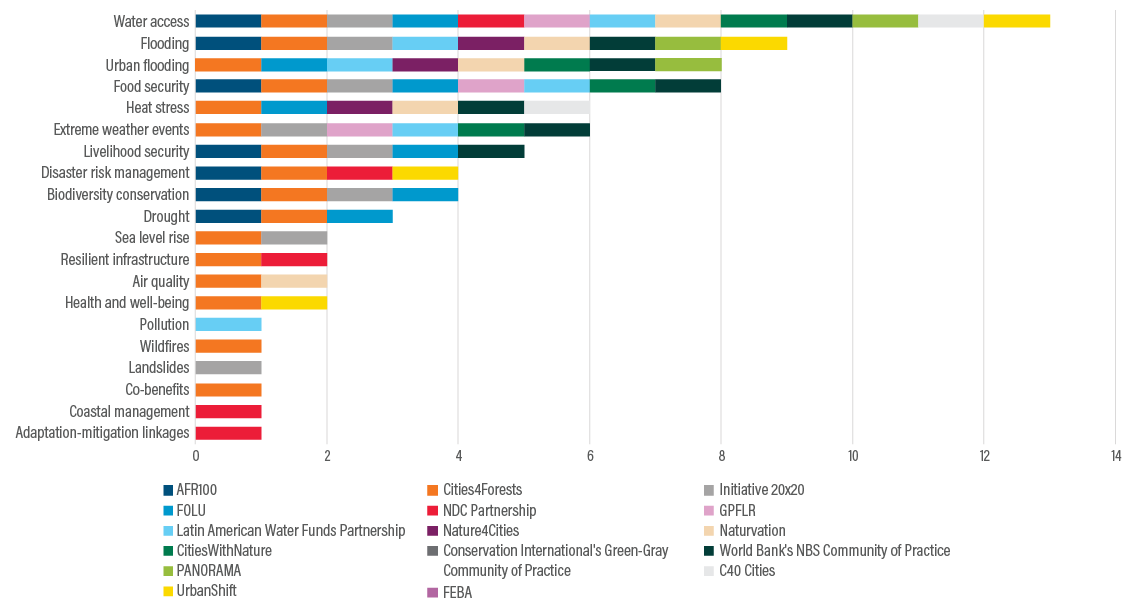

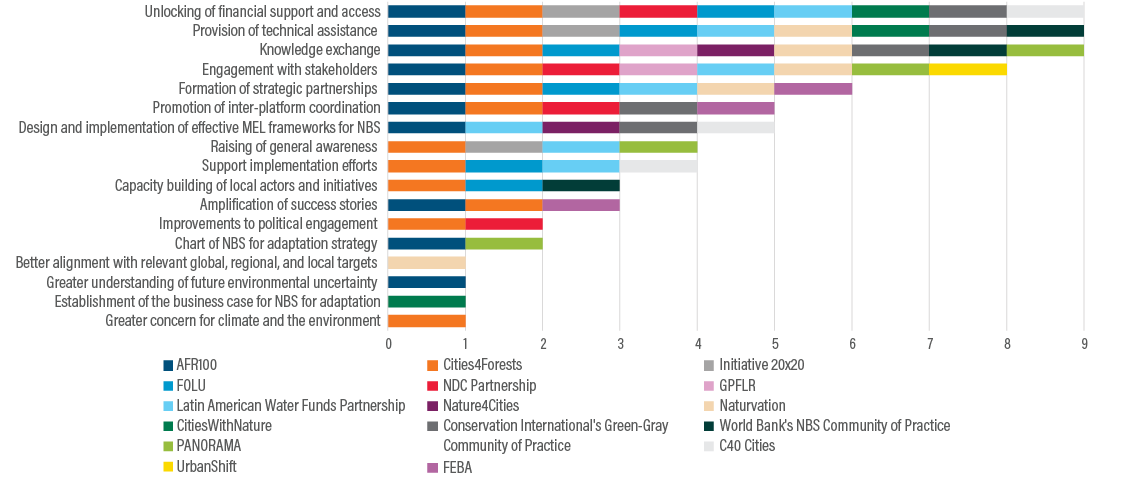

NBS initiatives have achieved important mitigation and sustainability outcomes; many could expand their impact by including adaptation. Secretariat staff of surveyed initiatives stated a strong interest in better including climate adaptation. Deliberately integrating adaptation into existing NBS initiatives would contribute to ecosystem health, social well-being, and climate resilience simultaneously.

This paper identifies key opportunities for NBS initiatives to contribute to adaptation outcomes:

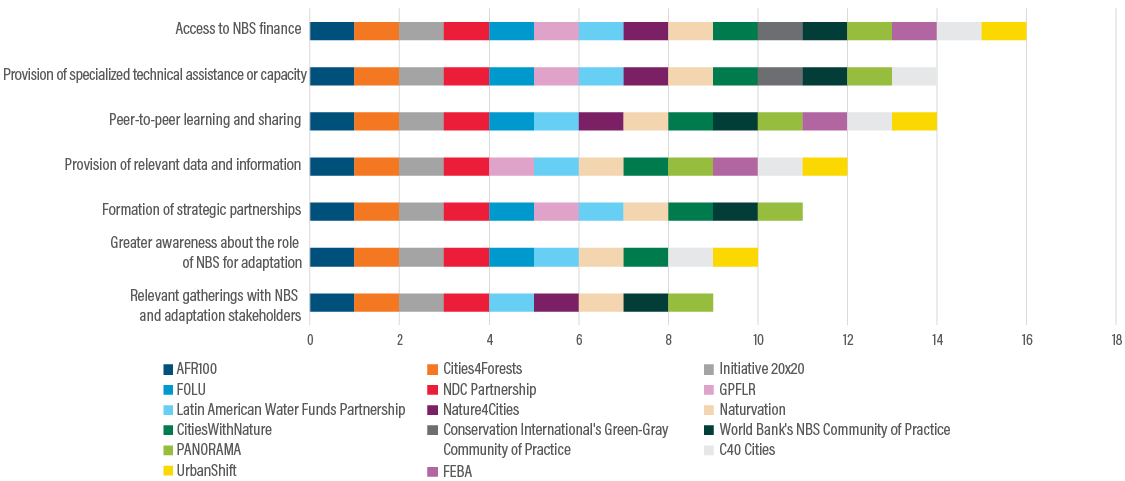

- Better coordinating among NBS initiatives to incorporate and accelerate climate adaptation efforts, especially by leveraging one another’s strengths: expertise in building strategic partnerships; providing specialized technical assistance and capacity building; promoting knowledge sharing; and actively engaging initiative stakeholders

- Sharing adaptation tools and processes from adaptation-focused organizations already integrating NBS

- Continuing to invest in NBS for adaptation pilots to open the door for larger initiatives while capitalizing on existing NBS initiatives’ expertise in accessing and mobilizing finance to attract more funding for adaptation

- Maximizing the adaptation benefits that NBS can deliver to groups that disproportionally bear the brunt of both climate impacts and ecosystem degradation

- Harnessing current political momentum surrounding NBS for adaptation by improving the evidence and socioeconomic cases for them and by better communicating their benefits

NBS initiatives face multiple barriers that limit their uptake of adaptation priorities. Examples include insufficient funding to expand their activities to include adaptation and limited technical expertise on adaptation.

Recommendations

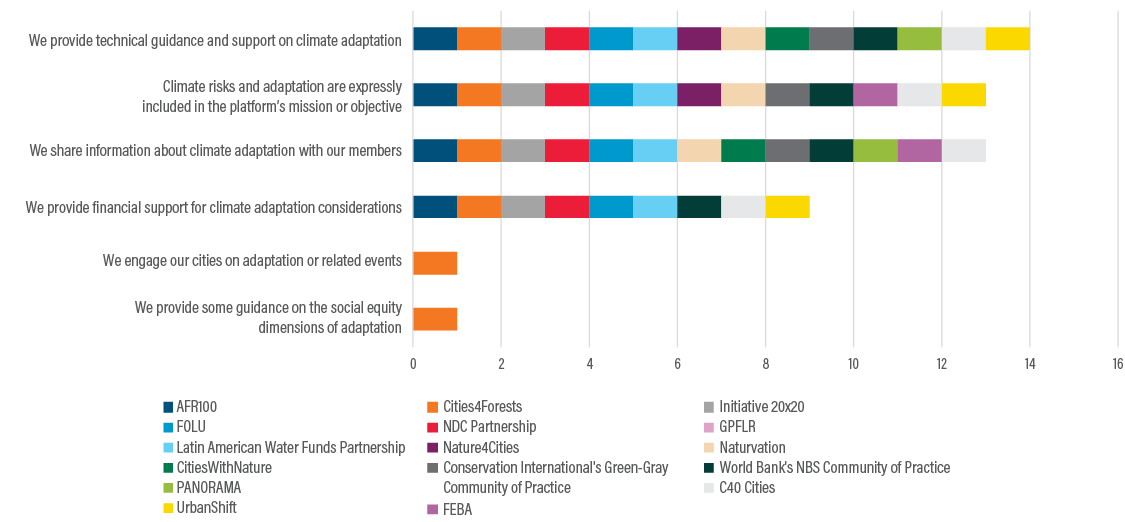

Initiatives should mainstream adaptation into their programs and activities, and better communicate the benefits of NBS for adaptation. Initiative secretariats should engage with adaptation partners and practitioners to build technical knowledge of and capacity for NBS for adaptation. They should also engage with communications specialists to better translate and raise awareness of NBS for adaptation benefits for a range of audiences.

Funders should consider investing in the expansion of existing initiatives as vehicles to incorporate and scale NBS for adaptation rather than creating new ones. Funders should encourage initiatives that largely focus on NBS for mitigation and other environmental services to include more content on adaptation, as this is a high-impact scaling opportunity to utilize initiatives’ strengths, user audiences, and established support resources.

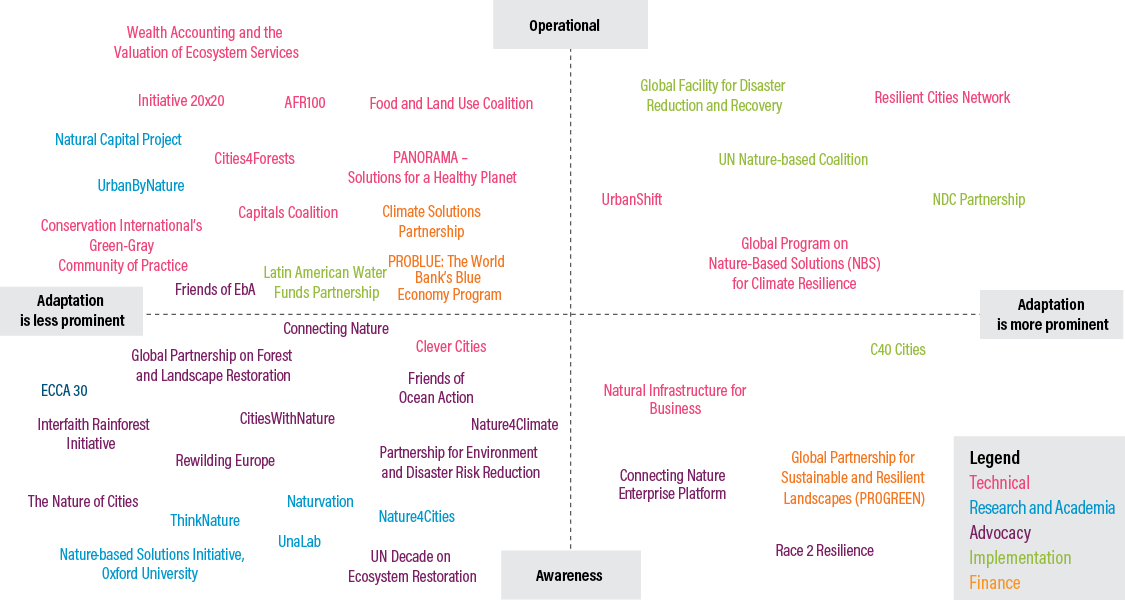

Funders and initiatives should promote collaboration among initiatives to fill gaps, leverage initiatives’ strengths, and develop global programs that can accelerate adaptation action. A wide range of NBS initiatives has proliferated worldwide, which can fragment their impacts as an abundance of options may make the landscape more difficult for users to navigate. Initiatives have an opportunity to clarify their roles and better organize efforts, for example, by meaningfully including local governments and organizations; funders could help by encouraging multi-partner proposals.

Funders and initiatives have an opportunity to enhance monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) of NBS for adaptation to strengthen the case for further action. Increased MEL and improvements to the evidence base on the benefits of NBS for adaptation will strengthen the economic, social, and environmental case for more and longer-term adaptation actions, capturing benefits for vulnerable groups. This integrated approach could result in more robust, equitable, and cost-effective solutions for cities, countries, and communities and help leverage more funding.

Funders and initiatives can do more to facilitate access to finance. NBS funders should provide flexible vehicles for financing the integration of adaptation into relevant pilots and programs, since expanding to include adaptation can enhance activities’ resilience and effectiveness. The intersectionality of NBS initiatives means they are uniquely positioned to help their users access and develop innovative financial mechanisms, which could be used to unlock climate finance for adaptation—especially from the private sector.

About This Paper

This paper seeks to understand the potential for existing NBS-centered initiatives to better incorporate climate adaptation, thereby contributing to broader adaptation efforts needed to combat the climate emergency. It explores the barriers these initiatives face to offering enhanced adaptation support, as well as existing and new opportunities for accelerating adaptation actions, while improving monitoring and evaluation and capturing lessons learned. Findings are based on an extensive literature review, a survey of the secretariat staffs of 16 initiatives, and follow-up interviews. Examples from three countries and one city illustrate the specific supporting roles that NBS initiatives can play in accelerating NBS for adaptation.

The target audiences for this paper are managers and coordinators of NBS initiatives interested in increasing their climate adaptation impact; as well as funders of NBS initiatives, including bilateral and multilateral donors. The authors also hope that the findings and recommendations in this paper are useful to adaptation practitioners and other funders in the conservation, adaptation, and sustainable development spaces, as well as city and national governments exploring nature-based measures to increase their climate resilience to mounting climate change impacts.