Executive Summary

Highlights

- While the world’s attention is on the global COVID-19 pandemic, climate change is also impacting human health and straining heavily burdened health services everywhere.

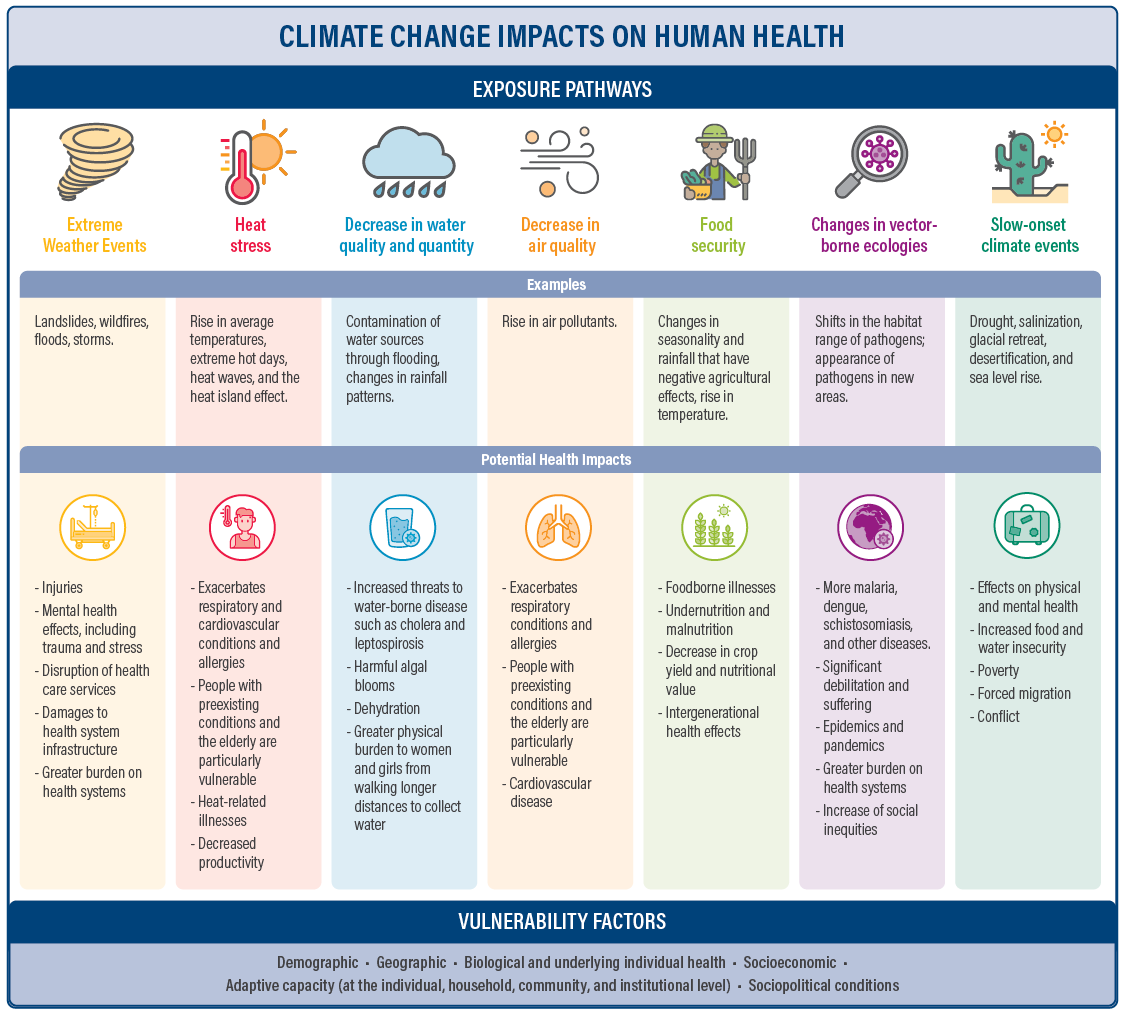

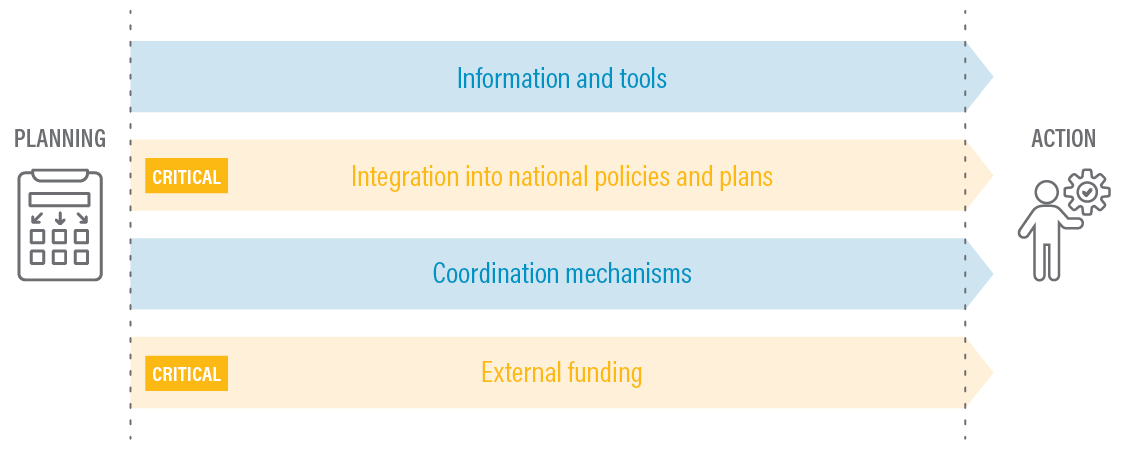

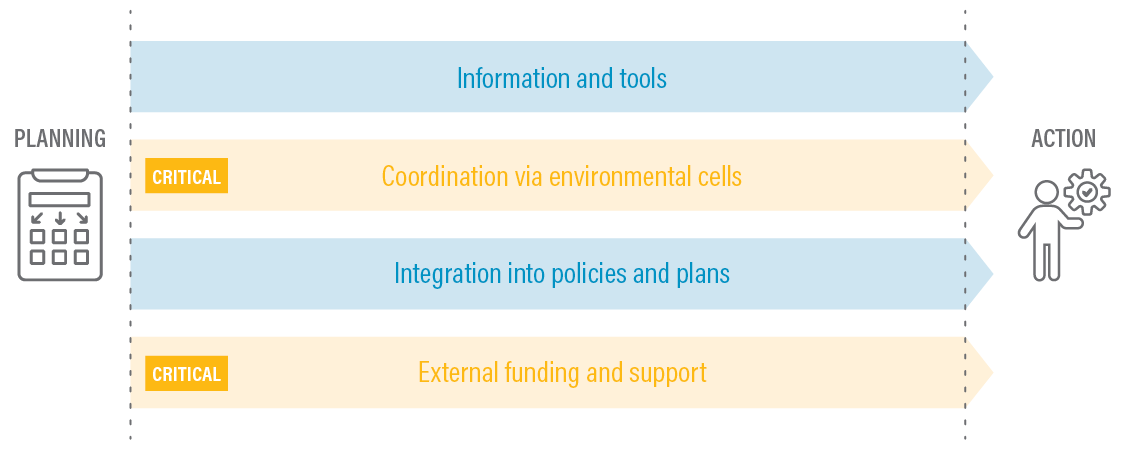

- Recognition of the linkages between climate change and health systems, such as shifts in vector-borne diseases and decreased access to services, is growing, yet many countries are still struggling both to mainstream, or integrate, climate adaptation into their health plans and to implement activities on the ground.

- This paper shares case studies from Fiji, Ghana, and Benin, three countries making progress with mainstreaming climate change adaptation into planning and implementation in health systems.

- These countries are instituting well-informed policies and plans, strengthening existing health systems, implementing and then expanding pilot projects, and demonstrating political leadership.

- However, challenges remain, including insufficient understanding and inadequate communication of linkages between climate change and health, poor data access and availability, and limited funding.

- Recommendations that emerge from these case studies include increasing human and financial resources; taking critical “no-regrets” actions now, such as increasing training of medical staff; funding and expanding successful pilot studies; establishing policy frameworks and collaboration mechanisms to mainstream adaptation; adopting a cross-sectoral approach; and linking health officials and adaptation planners.

The Global Pandemic Highlights the Need to Plan for Climate Risks in Health Systems

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the vulnerability of health systems. Without making changes to improve the robustness and resilience of health systems, these systems will be even less prepared to withstand the bigger shocks and stressors brought on by climate change. COVID-19 has laid bare the fact that few health systems are currently able to manage unexpected shocks well and that, as with climate change, the effects are disproportionally felt by the most vulnerable. Climate impacts are already undermining human health, threatening lives and health services everywhere. This upward trend is expected to intensify as global temperatures rise—which, among other problems, could help zoonotic diseases such as COVID-19 proliferate. The current crisis underlines the urgency with which countries must prepare for even greater challenges.

Health risks linked to climate change are many and varied. These include shifts in the geographical range and incidence of vector-borne diseases and foodborne illnesses, and increases in physical injuries, mental stress, and food insecurity and malnutrition. Climate events also impair critical health infrastructure, making it harder for people to access health care. Climate impacts are especially being felt by the most vulnerable, including people living in poverty, those who are ill or disabled, women, children, and the elderly.

This paper was largely drafted prior to the outbreak of COVID-19 but has benefited from our observation of the global response to the pandemic. Governments and organizations around the world have focused on finding ways to “build back better,” and initiatives have been launched to define and map out plans for achieving this goal. Leaders everywhere are recognizing that they will need to spend trillions of dollars responding to the direct and indirect effects of the novel coronavirus, such as widespread unemployment and economic crises, food security issues, and other challenges. But continuing to rebuild key systems—including in the health sector—in ways that do not help build resilience and that exacerbate inequality is unwise and shortsighted. Countries must instead build back their economies—including their health systems—better by preparing for a range of future shocks, including pandemics and climate change impacts.

This paper examines three countries—Fiji, Ghana, and Benin—that are currently working to make their health systems more resilient to climate change impacts. It explores the context, enabling factors, and challenges in each country, and identifies lessons learned and successful strategies that these countries have in common. It suggests ways in which health systems can be made more resilient by mainstreaming climate adaptation into health care and moving from planning to implementation. Many of the actions described could also apply to building resilience to infectious disease outbreaks and other health care challenges.

About This Working Paper

World Resources Institute (WRI), with support from Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development as a contribution to the NDC Partnership, is seeking to provide guidance to NDC Partnership member countries facing challenges mainstreaming adaptation across sectors and from the national to the local level. This paper is part of a series of case studies that apply WRI’s framework for successful mainstreaming (Mogelgaard et al. 2018) and identify elements essential for success. The series features the following:

- From Planning to Action: Mainstreaming Climate Change Adaptation into Development (Mogelgaard et al. 2018), which conducted a global analysis to identify factors that enable mainstreaming and implementation of adaptation activities

- Mainstreaming Adaptation in Action: Case Studies from Two States in India (Dinshaw et al. 2018), which examines mainstreaming at the state level in the livestock and forestry sectors

- Assessment of the Limits, Challenges, and Opportunities for Adaptation Mainstreaming in Brazilian Cities (Speranza et al. 2018), an internal report to the government of Brazil focused on mainstreaming from the national to the city level and the challenges of implementation

- Mainstreaming Climate Change Adaptation in Kenya: Lessons from Makueni and Wajir Counties (Chaudhury et al. 2020), which describes two local governments emerging as leaders in planning and implementing mainstreamed adaptation actions

- Building Coastal Resilience in Bangladesh, the Philippines, and Colombia: Country Experiences with Mainstreaming Climate Adaptation (Tye et al. 2020), a paper that examines three cases with on-the-ground actions to narrow the “implementation gap” between planning and action

Key Findings

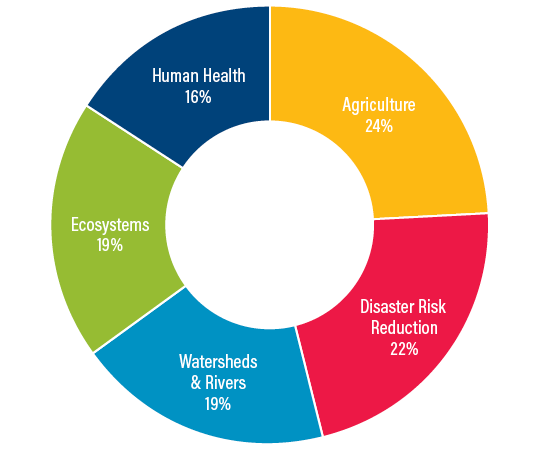

Linking climate adaptation and health policies is in high demand by countries, but effective action is lagging. More than half of the developing-country members of the NDC Partnership—a global coalition that helps countries find the technical support they need to draft, implement, and enhance their national climate commitments—have requested support through the partnership to strengthen their health systems’ resilience against the effects of climate change. However, many developing countries have made limited progress in developing plans, policies, and specific projects to address this complex issue.

Many countries’ health systems were already heavily strained even before the COVID-19 pandemic, with limited ability to address climate change impacts. The combination of COVID-19 and climate impacts will stress these systems even further.

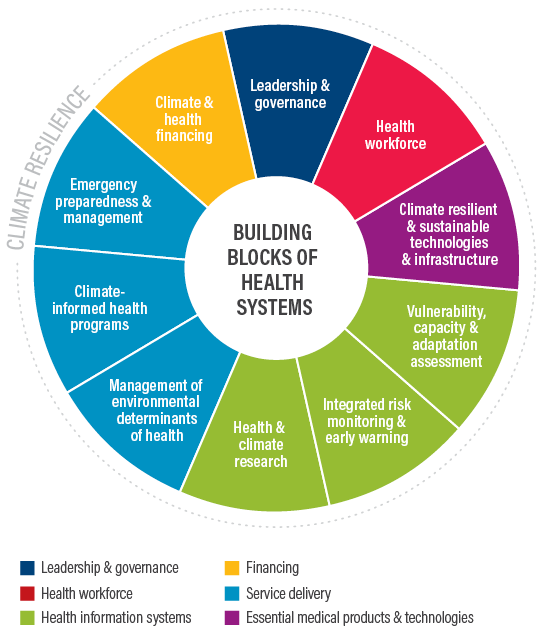

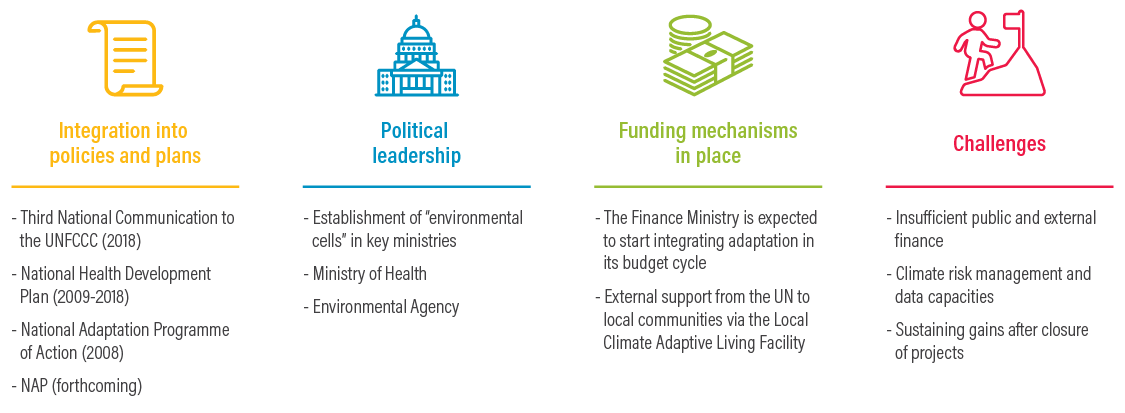

Case studies of Fiji, Ghana, and Benin demonstrate how climate adaptation can be mainstreamed into health policies, plans, and pilot projects, setting the stage for broader implementation of solutions. These countries are finding that strengthening health sector institutions, infrastructure, supply chains, and staff training is necessary to both build a more resilient foundation for the health sector and be in a better position to tackle climate change impacts and other types of shocks.

Pilot projects can demonstrate how mainstreaming climate adaptation into health policies can lead to broader, more comprehensive responses. In two of the three case study countries, Ghana and Benin, pilots helped to inform policies and plans, and wider implementation. However, lessons learned from such projects must lead to implementing and scaling up climate-resilient health policies if they are to be effective long-term.

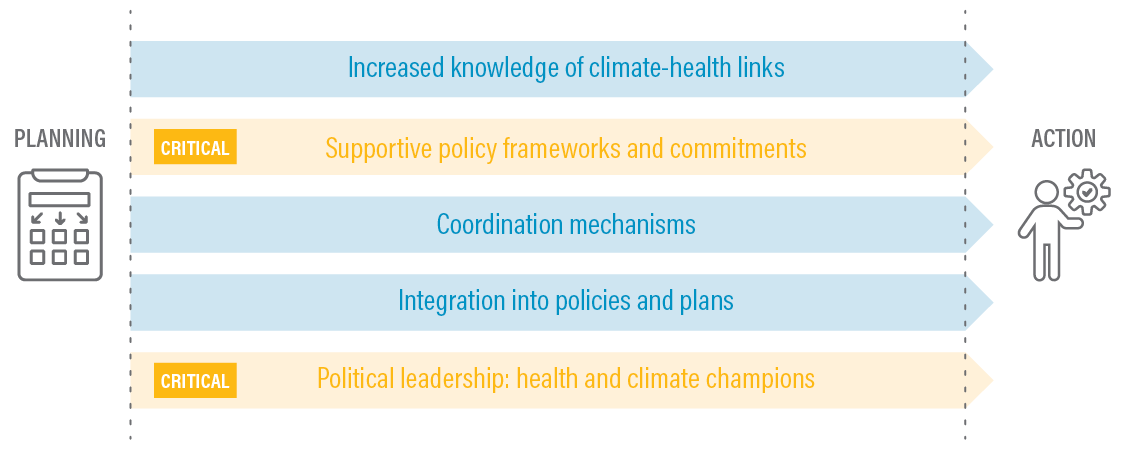

Political champions who understand the synergies between health and climate can play a crucial role in demonstrating leadership and providing guidance to develop and implement climate-resilient health policies.

Mechanisms like interagency climate committees are important for engaging key stakeholders in mainstreaming climate adaptation into the health sector. Improved coordination will help in adding adaptation to health sector plans and policies and in closing the implementation gap.

Challenges exist around translating and communicating technical terminology related to climate change into health policies. Limited access to and availability of data and funding to make the case for climate-related health risks present another barrier.

Recommendations

Enough information on climate-sensitive health risks exists to adopt critical no-regrets adaptation measures now to strengthen health care systems. Such measures need to be context-specific yet could incorporate best practices that have proved helpful elsewhere, such as training staff in vector-borne diseases and improving hospital infrastructure. Action should be taken immediately despite the need for better data and improved access to data in the case study countries and worldwide.

Policymakers can seize on the political moment created by the global pandemic to strengthen their countries’ abilities to respond to a range of other shocks and stressors—including the linked challenges of human health and climate change. The COVID-19 pandemic is shining a spotlight on the importance of robust and resilient health care systems. Increasing human capacity and financial resources is paramount for ensuring that effective measures are taken in time to better manage rapidly mounting climate-related risks to health.

Governments should establish policy frameworks and collaboration mechanisms to provide needed guidance and support to mainstream climate adaptation into the health sector. Formal frameworks and legislation help ensure that resources are dedicated to this issue.

Funders, including governments, should encourage and finance health projects and use lessons from these experiences to inform climate resilience planning in health sector plans and policies. As illustrated by the Fiji and Benin case studies, pilot projects can serve as a basis to expand broader national efforts and lead to cross-sectoral learning experiences.

Ministries of Health and adaptation planners should jointly design and implement health plans and policies that mainstream climate adaptation and demonstrate their feasibility through on-the-ground projects. Greater collaboration between these two areas of expertise can strengthen policies and implementation plans.

A cross-cutting, cross-sectoral approach that increases political will by engaging adaptation champions and key stakeholders, including subnational public and private actors, is needed to make health systems more resilient to climate change. Climate action advocates within and outside of the health sector are needed to galvanize broad support for strengthening health systems.