Executive Summary

Highlights

- Locally led adaptation, in which local actors have decision-making power in planning, implementing, and monitoring and evaluation, can play an essential role in achieving successful and sustainable adaptation.

- A literature review of over 70 evaluation materials found that local actors are often involved in adaptation interventions but not in making decisions around the finance, design, and implementation of adaptation activities that will affect them. Only 22 projects of those reviewed included notably strong locally led characteristics, although 138 projects out of 374 had some elements of locally led adaptation.

- Characteristics from the review that enable locally led adaptation include flexibility, investments in community leadership and local institutional capacities, and the reinforcement of adaptation across scales and programs.

- Barriers to locally led adaptation financing include lack of investment in local capacities to manage funds and adaptation processes, low levels of accountability from funders and implementing entities to local actors, and insufficient funding.

- Efforts to increase locally led adaptation action can focus on the following: encouraging flexible and iterative approaches to program design and implementation; including local actors in decision-making from start to finish; increasing technical capacity building; working with existing governance and finance mechanisms and networks to achieve scale and reduce transaction costs; and building the evidence base on locally led adaptation.

List of Abbreviations

- BRACED Building Resilience and Adaptation to Climate Extremes and Disasters

- CBA community-based adaptation

- CCCF County Climate Change Funds (initiative in Kenya)

- CDD community-driven development

- CSOs civil society organizations

- DCF Decentralising Climate Funds

- EbA Ecosystem-based Adaptation

- GCF Green Climate Fund

- GEF Global Environment Facility

- GIZ German Society for International Cooperation

- IIED International Institute for Environment and Development

- LDCs Least Developed Countries

- LoCAL Local Climate Adaptive Living Facility (a United Nations Capital Development Fund funding mechanism)

- NGO nongovernmental organization

Context

Despite the recognized need for climate adaptation efforts to be participatory, context-specific, and fully transparent, finance for local adaptation is still severely lacking, and the voices and concerns of local actors who are at the forefront of climate impacts have generally not been meaningfully included in deciding how interventions are financed, designed, and implemented (Mfitumukiza et al. 2020; Dinshaw and McGuinn 2019). The majority of adaptation planning still occurs at the international and national levels, with local institutions and actors participating on the margins and as beneficiaries instead of as agents of change (IIED forthcoming). More must be done to enable locally led adaptation, increase local efforts and capacities sustainably and equitably, and develop locally contextualized solutions.

About This Paper

This paper examines the existing literature on locally led adaptation, looking at efforts that have optimized finance through direct and consistent collaboration with local actors and identifying initiatives that embody locally led principles rather than traditional stakeholder consultation or participation. In line with the Global Commission on Adaptation’s Year of Action, the authors sought to identify projects and designs that aim to catalyze accelerated action and support for locally led adaptation. Partners in the commission seek to spur governments and funders to expand the financial resources that are available to local governments, community-based organizations, and other local actors, and help create structures that give local groups greater influence on decision-making over projects that directly affect them (GCA 2019). The primary audience for this paper is funders, international and local institutions, and decision-makers worldwide who are seeking to understand how to invest in locally led interventions that strengthen resilience, including climate resilience.

Where possible, the paper includes examples of projects or programs that have been responsive to local priorities and produced benefits (whether initial or over time) in terms of climate resilience. The authors synthesized the essential characteristics and program designs of international and country-driven investments that have reached the local level and enabled locally led adaptation. The application of this knowledge could enhance efforts to increase focus on—and finance for—durable, positive changes via locally led adaptation.

Key Findings

- Only a third of the projects (138 of 374) reviewed contained or documented any locally led elements explicitly, and a much smaller number (22) featured a locally led approach as a core or central component. Local actors are often involved in adaptation interventions as recipients but rarely in decision-making—including about how funding is allocated—or leadership roles throughout project life cycles.

- Barriers to locally led financing include a lack of investment in local capacities to manage funds and adaptation processes; low levels of accountability both upwards and downwards; limited amounts of funding making it to the local level; and funding used in a way that does not address or respond to local priorities.

-

There are a number of important characteristics that enable locally led adaptation:

- Institutional and technical capacity building tailored to different contexts, including increasing local capacities to access and manage finance, is closely tied with sustainability and scalability.

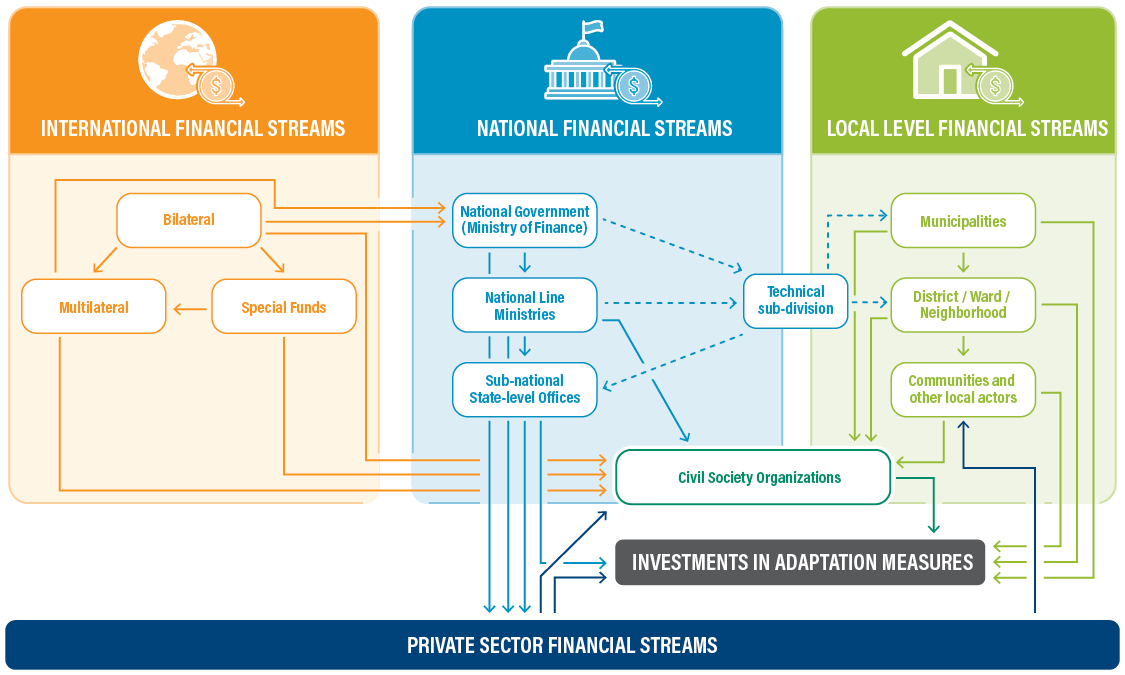

- Meaningfully including local leadership to tackle climate vulnerabilities requires making substantial changes in how global, national, and private finance is channeled and spent. These changes include incorporating devolved finance mechanisms and increasing financial flexibility in design and disbursement. Flexible funding allows local actors to manage funds in ways that best fit local needs, priorities, and evolving contexts. This flexibility, especially when combined with flexible design and implementation, can make it easier for interventions to address different climate scenarios.

- Existing governance and finance mechanisms, networks, federations, and institutions that reach down to local levels can work together and be expanded to achieve economies of scale and sustainable results, rather than starting new mechanisms or institutions. Establishing intergovernmental and public-private mechanisms or alliances can lower the traditionally high transaction costs associated with capacity building, as overlaps in responsibilities and complementary skills are taken advantage of and pave the way for scaling interventions.

- Reinforcing and scaling adaptation action requires awareness and coordination from all levels of government. Local authorities play a central role in reinforcing and scaling adaptation, as do civil society actors who help ensure accountability and the flow of information.

- Ensuring that policy objectives are clear and linking activities and adaptive management approaches that feature iterative learning from the local to the national level can foster enabling environments, encourage local actors’ agency, and set up the institutional networks needed for long-term resilience.