Executive Summary

Highlights

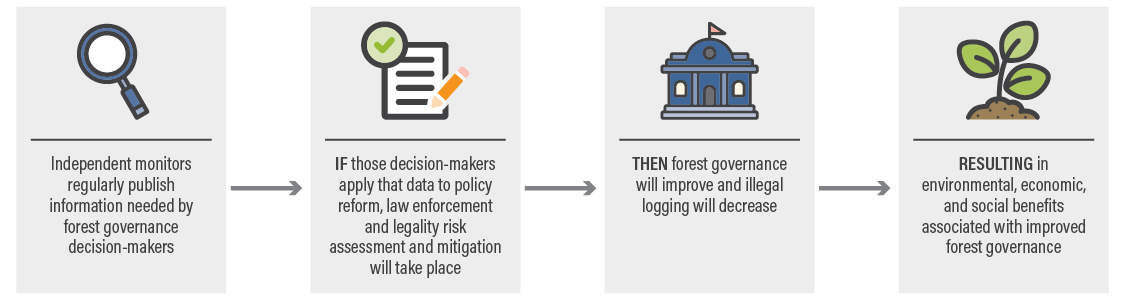

- Launched by international donors and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) more than 20 years ago, independent forest monitoring (IFM) is a key component of international strategies aiming to improve forest governance and tackle illegal logging.

- New regulations and processes now provide opportunities to expand IFM geographically and apply it to agricultural commodities.

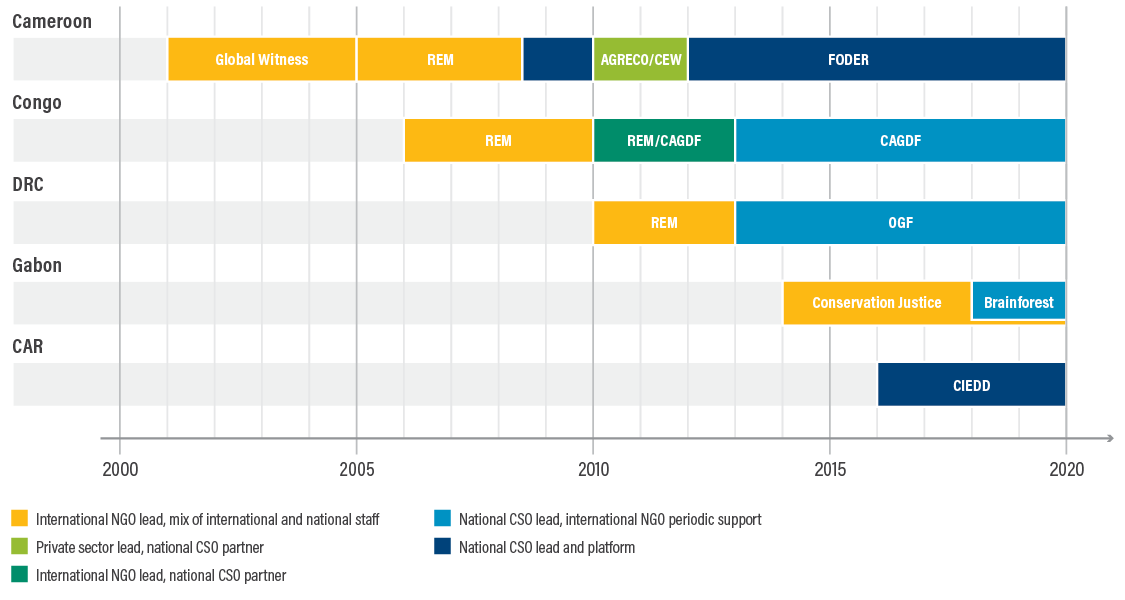

- This working paper evaluates the achievements of IFM in the Congo Basin based on the analysis of 469 IFM mission reports published by 11 IFM organizations between 2001 and 2020.

- Despite political resistance, IFM organizations have delivered significant outcomes including the withdrawal of illegal forest titles and adoption of new ministerial orders improving forest legality and forest governance overall.

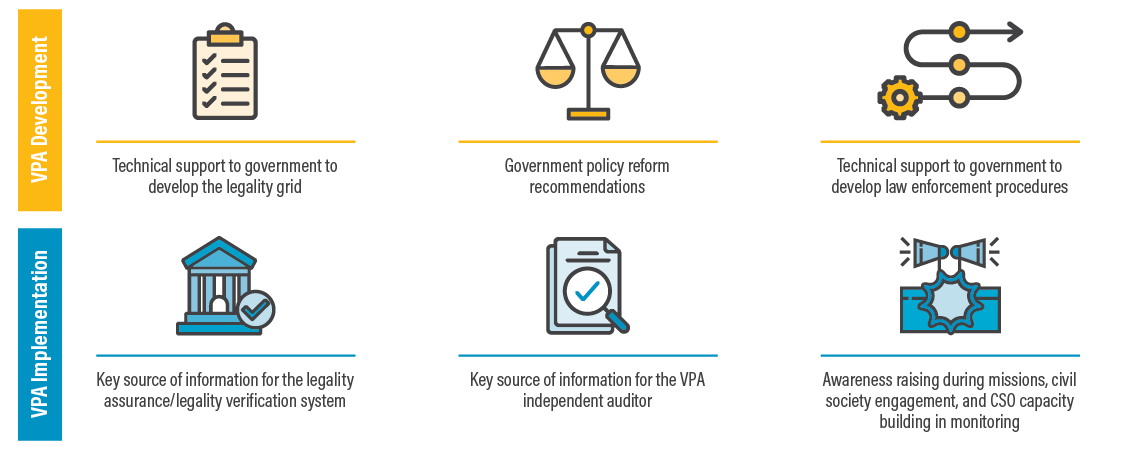

- The lessons learned from 20 years of IFM of illegal logging in the Congo Basin can inform the development of emerging forms of IFM; e.g., determining if illegal forest clearing is occurring within agricultural developments, or determining which REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) projects are complying with safeguards and achieving promised benefits.

- To improve the efficiency of IFM in the region, expand the model geographically, and move it beyond timber, donors and policymakers should support policy and legal reform institutionalizing IFM, propose long-term funding mechanisms for IFM, and promote standardized monitoring and evaluation processes across IFM projects.

- IFM organizations should also improve the utility of IFM data to enforce demand-side measures by further improving IFM efficiency, data quality, and standardization.

Context

Forest crime—including illegal logging, trade in illegally sourced timber, and illegal deforestation for commodities—remains a major obstacle in reducing tropical forest loss. It directly degrades forest ecosystems and inflicts the first cut on forests that are too often further degraded, burned, and cleared. Illegal logging also hurts local and national forest economies, is frequently linked to transnational criminal networks, and, in some places, fuels violent conflict and terrorism. For businesses trying to operate within the law, illegal logging gives unfair financial advantage to those who break the law.

While there is no universal definition of illegal logging, the Forest Legality Initiative of the World Resources Institute (WRI) defines the term to “include all practices related to the harvesting, processing, transport, sale, and purchase of timber, as defined in the country of origin, as well as any violations of a country’s legal framework that may occur throughout the supply chain” (Noguerón et al. 2018).

The extent of illegal logging activities is difficult to document, therefore making it difficult to monitor. Nevertheless, over the past two decades, the “adoption of timber legality measures […] involv[ing] independent monitors has strengthened the political basis for action” (Barber and Canby 2018). Since the late 1990s, IFM has been a “feature of international efforts to improve forest governance and reduce illegal logging” and has taken different shapes and forms in different countries at different times (Brack and Léger 2013).

The Research Problem

As new regulations on deforestation-free commodities provide opportunities to expand IFM beyond timber, it is critical to reflect on the 20-year experience of IFM in the timber sector. While the concept of IFM first emerged in Cambodia, it is in the Congo Basin where IFM has further developed over the past 20 years. Understanding how the IFM concept emerged and evolved in the Congo Basin, what IFM organizations have achieved, and what challenges they face is key to improving IFM and informing its expansion to other regions and commodities.

About This Working Paper

WRI and its partners, Field Legality Advisory Group (FLAG) and Resource Extraction Monitoring (REM), evaluated the achievements of IFM in the Congo Basin since 2000. This analysis was based on information from 469 IFM mission reports published by 11 IFM organizations between 2001 and 2020. In this paper, we identify key challenges faced by IFM organizations and propose recommendations for practitioners, policymakers, NGOs, and donors to improve the efficiency of IFM in the region, expand the model geographically, and move it beyond timber.

Key Findings

Despite challenges in navigating relationships with governments, IFM organizations have delivered significant outcomes including, but not limited to, the withdrawal of illegal forest titles and the adoption of new ministerial orders improving forest legality and forest governance overall. Our analysis reveals that more reports were published in the early years of IFM, when fewer IFM organizations were active and fewer countries covered. The highest number of IFM missions was completed in Cameroon, where IFM began, with an average of 14 percent of forest management units visited each year between 2007 and 2013.

Recommendations

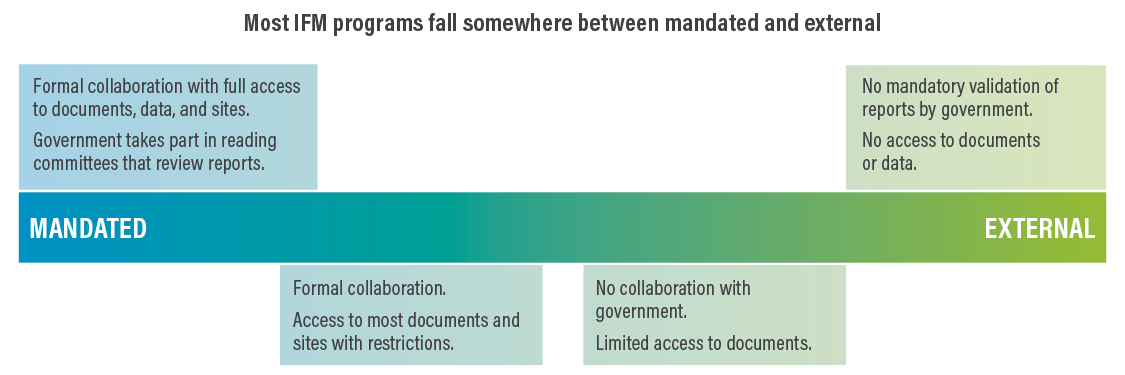

We propose solutions to tackle political resistance as well as other challenges faced by IFM organizations, including difficulties with accessing information and maintaining credibility. We also suggest ways to improve IFM efficiency, funding, and visibility before expanding the model geographically and moving it beyond timber. We recommend the following:

- Institutionalization of IFM in national laws and international regulations

- Adoption of IFM quality standards

- Development of an international IFM community of practice, and of more subnational IFM networks

- Negotiation of good memorandums of understanding between IFM organizations and governments supporting better access to information for IFM organizations

- Involvement of other ministries beyond the Ministry of Forests

- Communication of IFM findings to a broader international audience

- Improvement of the utility of IFM data for implementation and enforcement of demand-side measures

- Collection of more data where timber is stored, such as in ports and log yards, in addition to data collected in forests

- Investment in monitoring and evaluation using a regionally standardized set of indicators

- Development of a long-term funding mechanism for IFM

- Further investment in IFM capacity building, including how to best use new technologies

- Investment in capacity building for importers to use IFM data