Foreword

As this report is being released, the price of gold hit a record high of almost $2,100 per ounce in August. Gold prices had been rising for years but the threat to economies from the novel coronavirus led to a surge in prices — up about 35 percent this year — as investors sought the perceived safety of gold. As prices rise, so does demand and mining. These circumstances make this report on the effects of mining on indigenous people and their lands in the Amazon particularly timely.

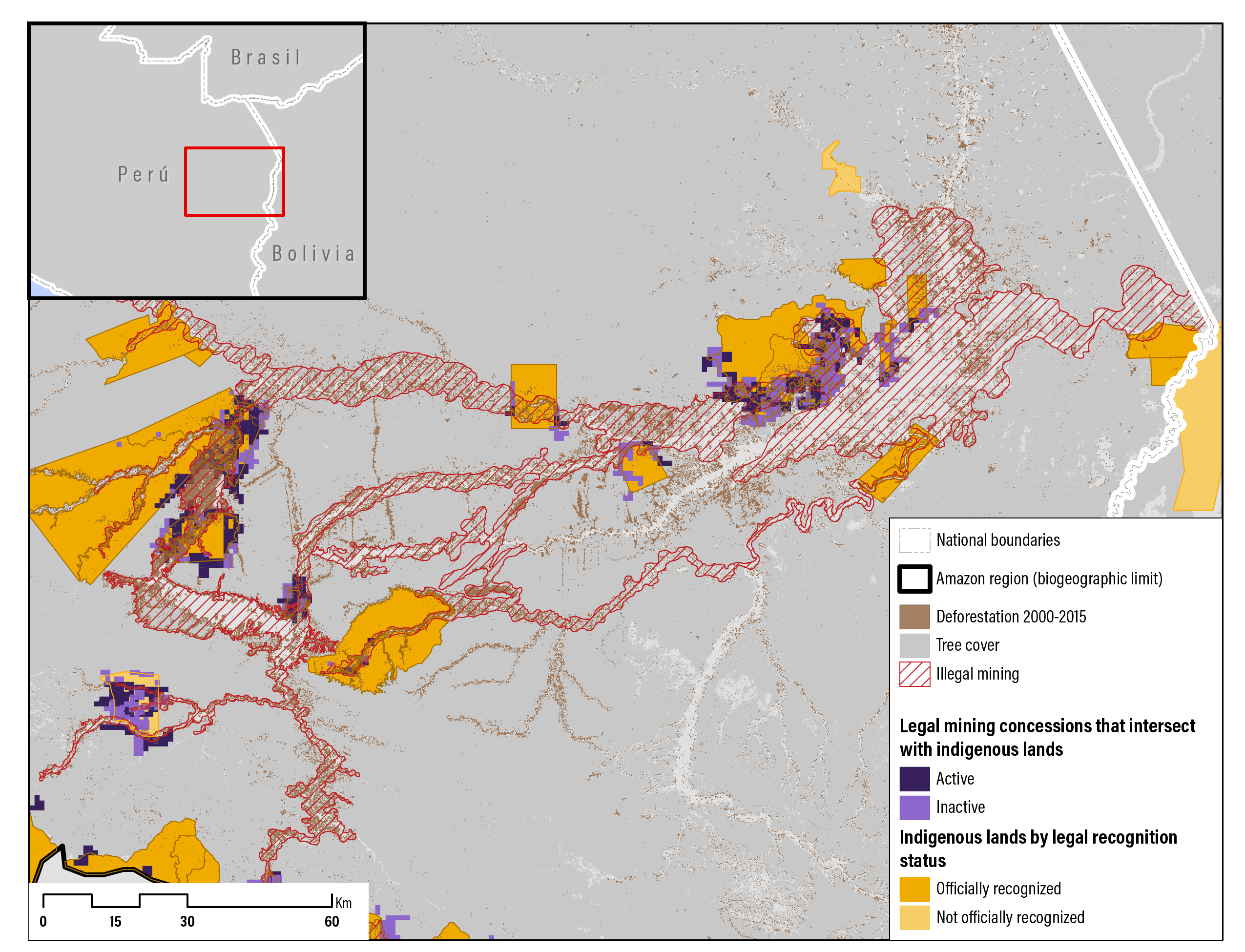

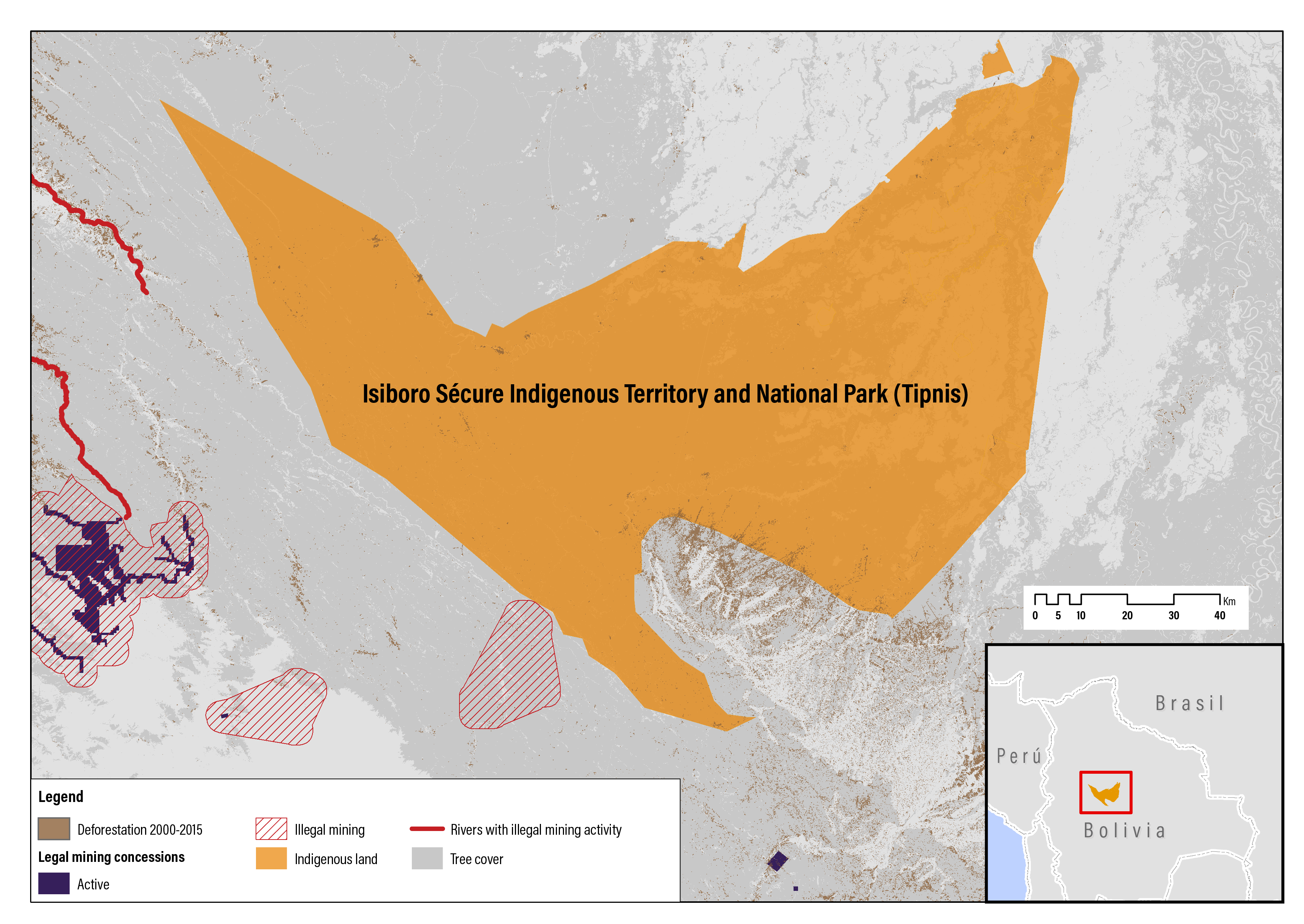

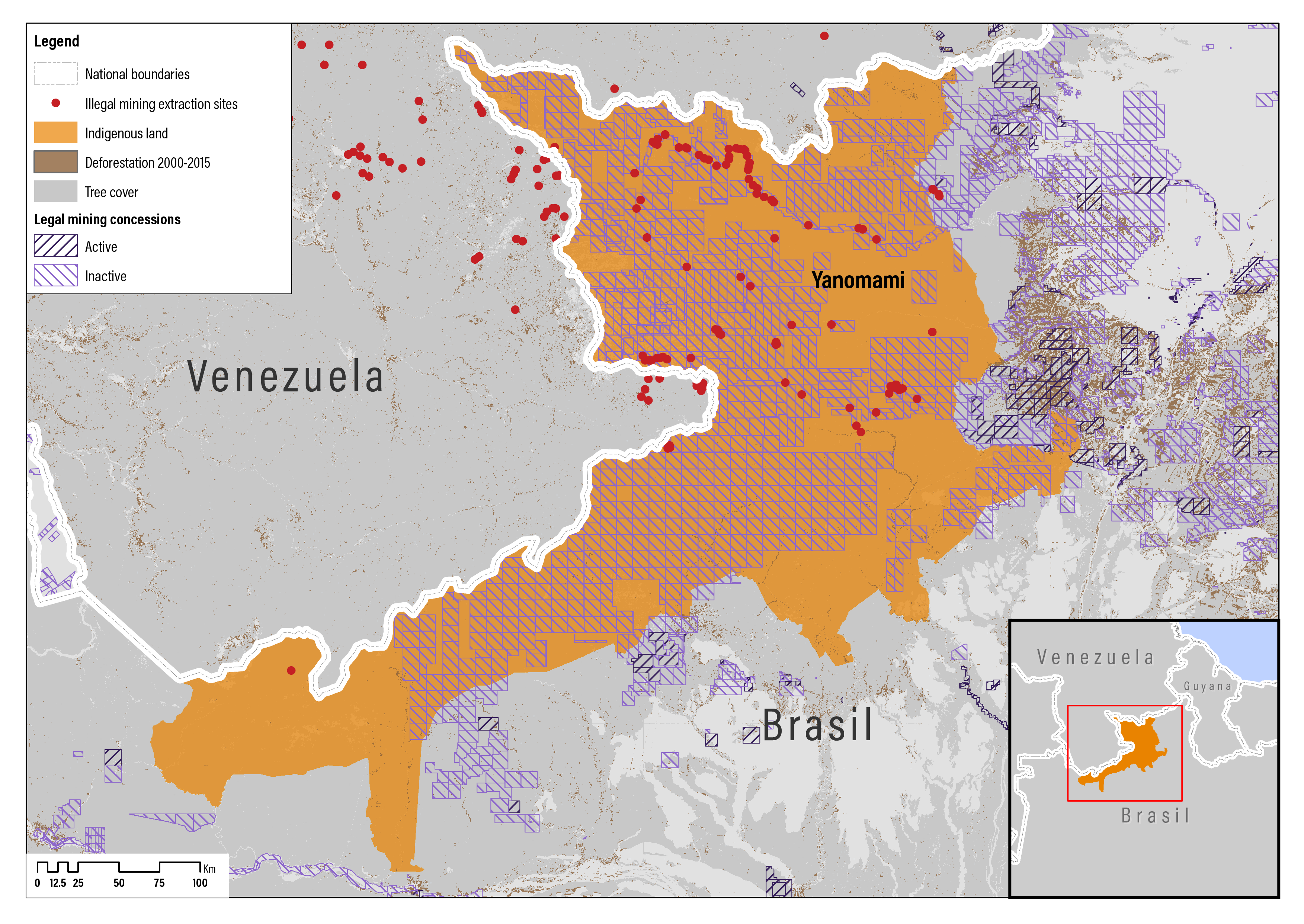

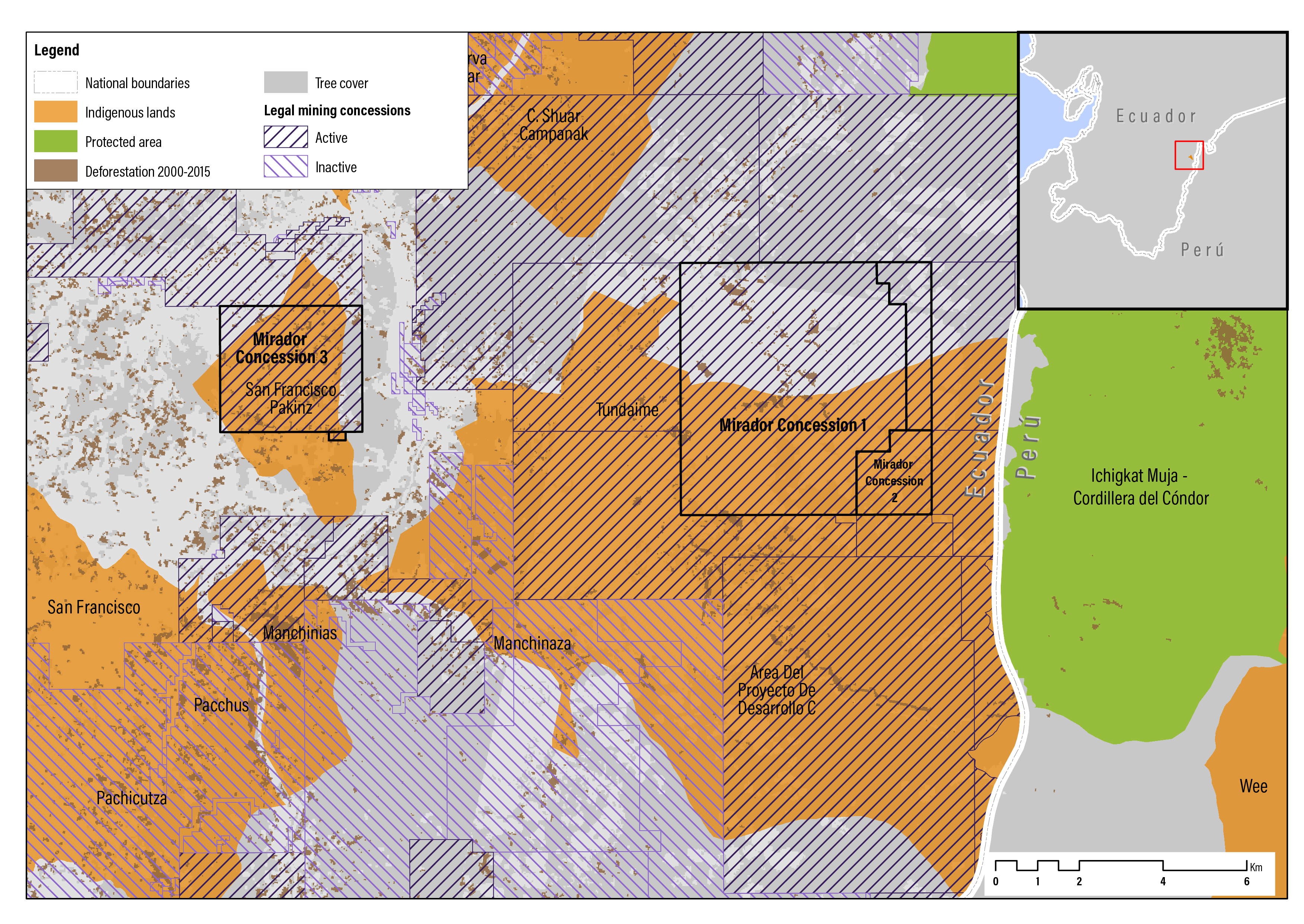

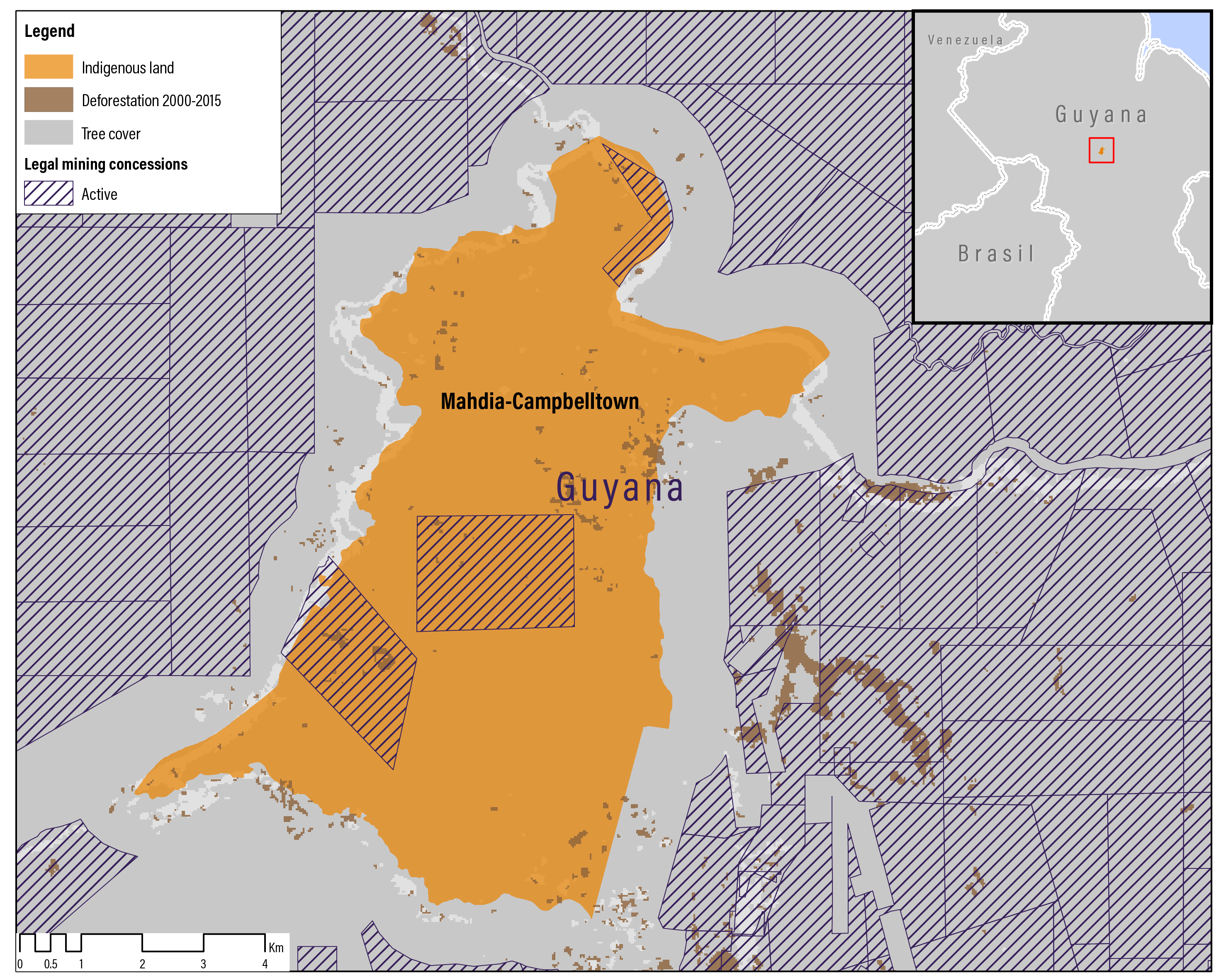

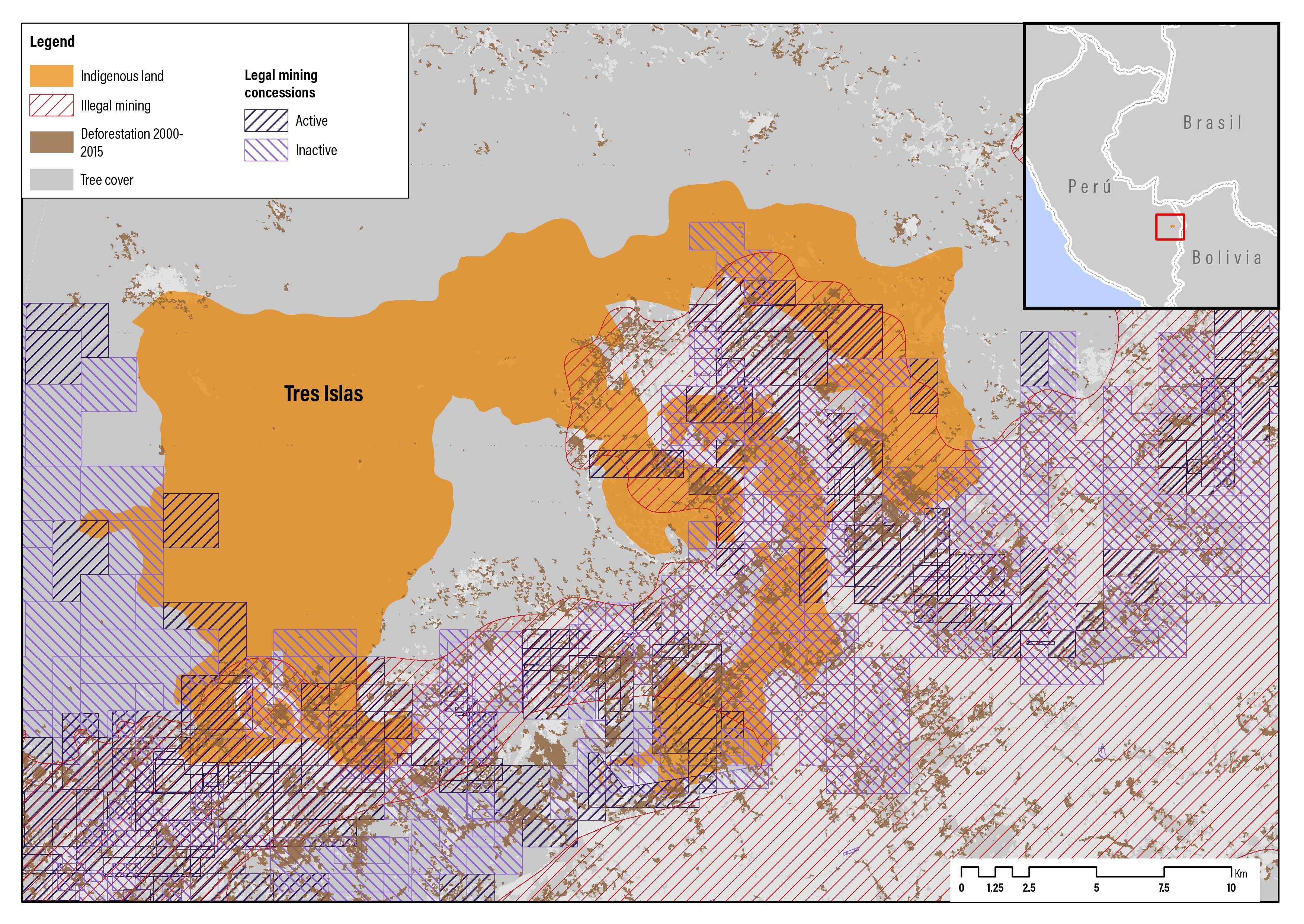

We know from previous WRI research that deforestation rates on indigenous lands in the Amazon are sharply lower than on similar land not managed by indigenous people. Now we have learned from this report that industrial mining concessions and illegal small-scale mining occur on more than 20 percent of indigenous lands in the Amazon and that deforestation rates on indigenous lands with mining are significantly higher than on indigenous lands not affected by mining.

The Amazon is home to about 1.5 million indigenous people. The forest is their home and source of livelihood. Mining is environmentally destructive and brings social and health risks. Environmental degradation leads to the loss of critical ecosystem services—such as water flow regulation, biodiversity and carbon sequestration—that benefit indigenous people and all humanity. Mining also leads to conflict, especially between miners and indigenous people. According to Global Witness, mining was the deadliest sector for land defenders in 2018 and 2019.

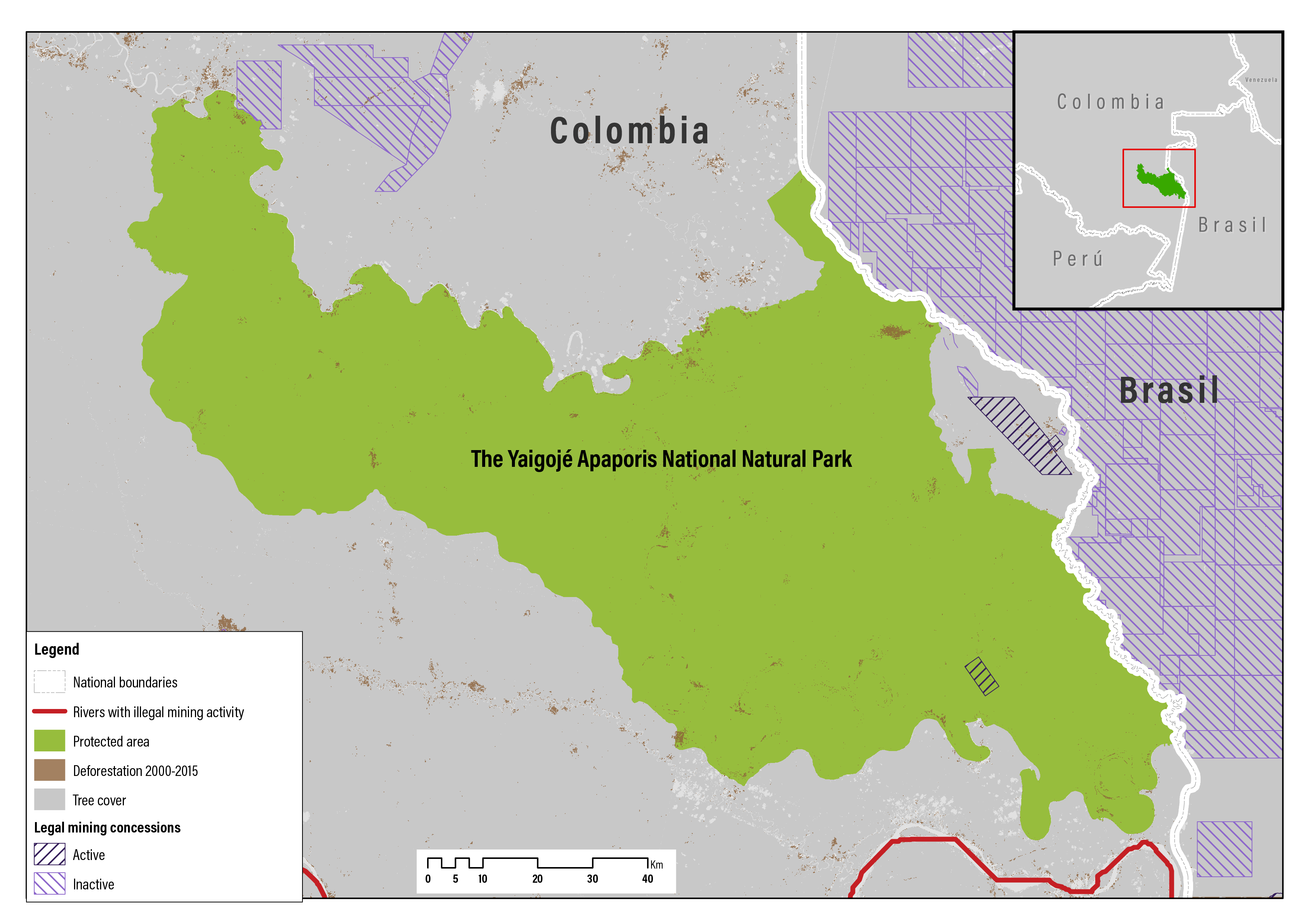

This report finds that while laws in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, and Peru recognize some land rights for indigenous people, they do not provide the legal protections needed for them to secure their lands and take charge of their own development. For example, of these countries, only Guyana recognizes a limited form of consent, and only Colombia provides the right of first refusal when the government grants a mining concession on their lands. Yet mining companies often have sweeping rights to enter and use indigenous land for their operations.

The case studies for this report reveal that some indigenous people take extraordinary measures to protect their lands from mining. In Peru, for example, the Tres Islas indigenous communities persuaded domestic courts to declare 127 mining concessions on their land null and void. In Colombia, when a mining company sought a concession on their land, the Yaigojé Apaporis people successfully convinced the government to designate their land as a national natural park where mining is prohibited.

The findings have implications for indigenous people, governments, development agencies, mining companies and civil society organizations to correct the large power discrepancies between indigenous people and miners. It calls on governments to enact legislation that recognizes additional land and mineral rights for indigenous people, establish strong social and environmental safeguards, and better monitor mining to ensure compliance with national laws. It calls on mining companies to respect indigenous rights and provide indigenous people with fairer shares of mining benefits. And it calls for indigenous people to build the skills needed to protect themselves from harm.

Decisionmakers around the world have an opportunity to support indigenous people and protect forests. With mining rapidly expanding deeper into the Amazon, it’s time to act. Not doing so would have a massive cost to indigenous people and the forest—a cost much greater than gold.

Andrew Steer

President

World Resources Institute